Pastoral

Edna St. Vincent Millay

1892 to 1950

If it were only still!—

With far away the shrill

Crying of a cock;

Or the shaken bell

From a cow’s throat

Moving through the bushes;

Or the soft shock

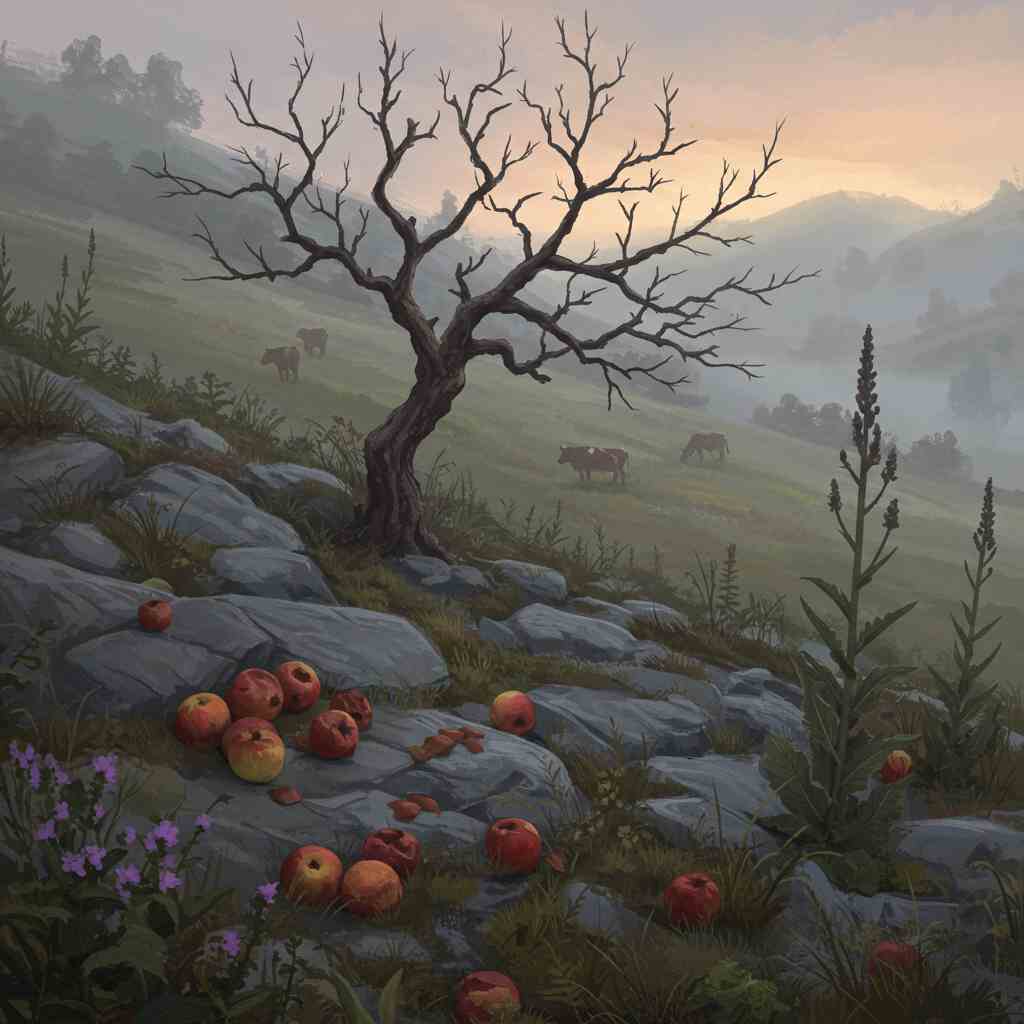

Of wizened apples falling

From an old tree

In a forgotten orchard

Upon the hilly rock!

Oh, grey hill,

Where the grazing herd

Licks the purple blossom,

Crops the spiky weed!

Oh, stony pasture,

Where the tall mullein

Stands up so sturdy

On its little seed!

Edna St. Vincent Millay's Pastoral

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Pastoral is a deceptively simple poem that captures a profound yearning for stillness, nature, and an escape from the clamor of modern life. Written in the early 20th century—a period marked by rapid industrialization, urbanization, and the aftermath of World War I—the poem reflects a pastoral ideal, a literary tradition that idealizes rural life as a counterpoint to the chaos of civilization. However, Millay’s treatment of the pastoral is neither naïve nor purely idyllic; instead, it is tinged with melancholy, a recognition of the fleeting nature of peace and the impossibility of fully retreating into silence. Through careful attention to sound, imagery, and structure, Millay crafts a poem that is as much about absence as it is about presence, as much about what is lost as what remains.

The Pastoral Tradition and Millay’s Subversion

The pastoral, as a literary form, dates back to classical antiquity, with poets like Theocritus and Virgil idealizing the simplicity and harmony of rural existence. In English literature, the tradition was revived during the Renaissance and Romantic periods, with poets such as Marlowe, Wordsworth, and Keats portraying nature as a sanctuary from societal corruption. Millay, writing in the modernist era, engages with this tradition but complicates it. Unlike the Romantics, who often depicted nature as a sublime and redemptive force, Millay’s pastoral scene is fragile, almost ghostly. The poem does not celebrate an untouched wilderness but rather a landscape marked by human absence—a "forgotten orchard," a "hilly rock," a "stony pasture." These are not fertile Edens but marginal spaces, where nature persists despite neglect.

The opening line—"If it were only still!"—immediately establishes a tone of longing. The speaker does not begin by describing an achieved tranquility but rather a desired one. The conditional "if" suggests that such stillness is elusive, perhaps already lost. This distinguishes Millay’s pastoral from more conventional ones; hers is not a poem of contentment but of yearning.

Sound and Silence: The Poem’s Auditory Landscape

One of the most striking features of Pastoral is its attention to sound—or rather, the absence of it. The speaker longs for a world where the only noises are those of rural life: the distant "shrill / Crying of a cock," the "shaken bell / From a cow’s throat," or the "soft shock / Of wizened apples falling." These sounds are not disruptive but organic, woven into the fabric of the landscape. They are also intermittent, suggesting a rhythm dictated by nature rather than human industry.

The contrast between these soft, natural sounds and the implied noise of modernity is crucial. The early 20th century was an era of mechanized sound—factories, automobiles, telephones—and Millay’s poem can be read as a quiet resistance to this cacophony. The "shrill" cry of the rooster is far away, the cow’s bell moves "through the bushes" as if muffled, and the falling apples land with a "soft shock." Even the mullein, a hardy weed, stands "sturdy / On its little seed," a quiet triumph of persistence. The poem, then, is not just a depiction of rural life but an argument for its value, a plea for the preservation of quietude in an increasingly loud world.

Imagery of Decay and Resilience

Millay’s imagery is rich with contradictions—beauty coexists with decay, vitality with abandonment. The "wizened apples falling / From an old tree / In a forgotten orchard" suggest both the passage of time and the endurance of nature. The apples are not ripe and plump but "wizened," shrunken with age, yet they still make a sound as they fall. The orchard is "forgotten," yet it continues to exist, its trees still bearing fruit in their own diminished way.

Similarly, the "grey hill" where the herd grazes is not lush but sparse, the animals feeding on "the purple blossom" and "the spiky weed." Even the mullein, often considered a weed, is portrayed with dignity, standing "up so sturdy / On its little seed." These images resist the conventional pastoral’s tendency toward idealization. Millay’s nature is not endlessly bountiful but resilient in its austerity.

This tension between decay and resilience may reflect Millay’s own historical moment. Written in the aftermath of World War I, a time of profound disillusionment, the poem’s muted beauty suggests a world that has been wounded but endures. The pastoral, then, is not an escape from history but a way of reckoning with it—acknowledging loss while finding solace in what remains.

Structure and Rhythm: Mimicking the Uneasy Quiet

The poem’s structure reinforces its themes. The lines are short and irregular, avoiding a predictable meter, which creates a sense of spontaneity, as if the speaker’s thoughts are unfolding in real time. The enjambment—lines spilling into one another without punctuation—mimics the fluidity of natural sounds. For example:

"Or the soft shock

Of wizened apples falling

From an old tree

In a forgotten orchard

Upon the hilly rock!"

The lack of pauses between "shock," "falling," and "old tree" makes the description feel immediate, as if the reader is witnessing the apples’ descent in real time. At the same time, the exclamation at the end—"Upon the hilly rock!"—suggests a sudden emotional surge, a moment where the speaker’s longing becomes almost palpable.

The second stanza shifts from auditory to visual imagery, focusing on the "grey hill" and the "stony pasture." The tone becomes more contemplative, almost reverent, as the speaker observes the grazing herd and the stubborn mullein. The poem’s closing lines—"Stands up so sturdy / On its little seed!"—carry a quiet triumph, celebrating resilience in the face of harsh conditions.

Biographical and Philosophical Undercurrents

Millay herself was no stranger to contrasts—between city and country, fame and solitude, vitality and melancholy. Known for her bohemian lifestyle and feminist poetics, she often explored themes of desire, independence, and transience. While Pastoral is less overtly personal than some of her other works, it aligns with her broader fascination with fleeting beauty and the tension between human presence and nature.

Philosophically, the poem resonates with the modernist preoccupation with fragmentation and impermanence. Unlike the Romantics, who sought transcendence in nature, Millay’s speaker seems aware that the stillness they desire is fragile, perhaps already lost. This awareness lends the poem its poignant edge—it is not a celebration of an unspoiled world but an elegy for one that is slipping away.

Conclusion: The Pastoral as Longing

Pastoral is a poem of quiet intensity, a meditation on the human desire for stillness in an ever-noisier world. Millay neither fully embraces the pastoral ideal nor rejects it; instead, she presents it as a fragile, fleeting possibility. The sounds and images she evokes—the distant cock’s cry, the falling apples, the sturdy mullein—are not just descriptions of rural life but symbols of resilience in the face of neglect and time.

In this way, the poem transcends its immediate context, speaking to any reader who has yearned for a moment of quiet, a respite from the relentless pace of modern existence. It is a reminder that beauty persists even in forgotten places, that stillness, though elusive, is worth seeking. Millay’s Pastoral does not offer easy consolation, but in its delicate balance of longing and acceptance, it captures something deeply true about the human condition—our eternal search for peace in an imperfect world.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.