Spring it is Cheery

Thomas Hood

1799 to 1845

Spring it is cheery,

Winter is dreary,

Green leaves hang, but the brown must fly;

When he's forsaken,

Wither'd and shaken,

What can an old man do but die?

Love will not clip him,

Maids will not lip him,

Maud and Marian pass him by;

Youth it is sunny,

Age has no honey,—

What can an old man do but die?

June it was jolly,

Oh for its folly!

A dancing leg and a laughing eye;

Youth may be silly,

Wisdom is chilly,—

What can an old man do but die?

Friends, they are scanty,

Beggars are plenty,

If he has followers, I know why;

Gold's in his clutches,

(Buying him crutches!)

What can an old man do but die?

Thomas Hood's Spring it is Cheery

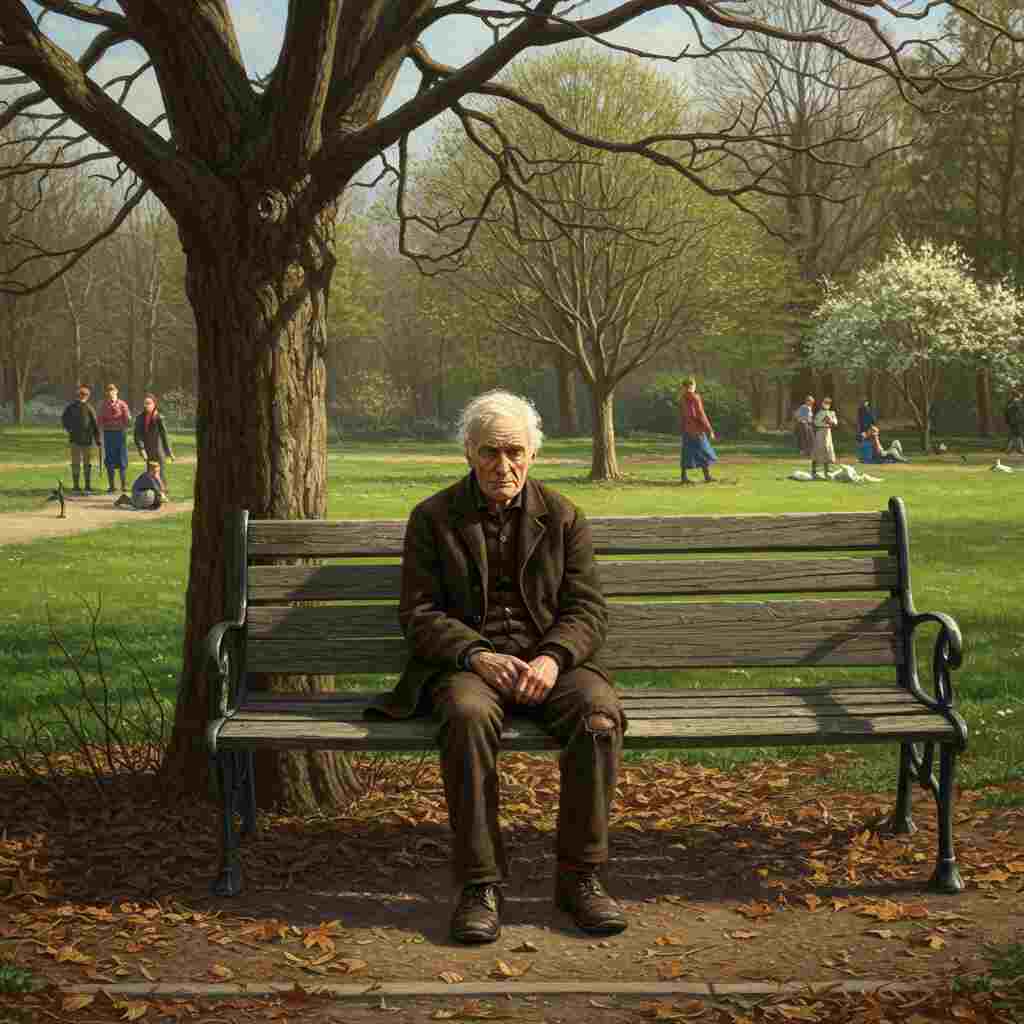

Thomas Hood (1799-1845), often relegated to the periphery of Romantic literary discourse, crafted poetic works that combined remarkable verbal dexterity with profound emotional depth. His poem "Spring it is Cheery" exemplifies his ability to juxtapose seemingly lighthearted constructions with thematic gravitas. This analysis seeks to excavate the multifaceted dimensions of Hood's deceptively simple verses, tracing the poem's engagement with temporality, mortality, and the human experience of aging while contextualizing it within both Hood's broader oeuvre and the transitional period between Romantic and Victorian literary sensibilities.

"Spring it is Cheery" presents a searing meditation on the dichotomy between youth and age, vitality and decline, rendered through seasonal metaphors and an insistent refrain that heightens its emotional potency. The poem's superficial musical quality, characterized by its lilting meter and playful rhymes, exists in striking tension with its somber contemplation of life's inevitable progression toward death. This interplay between form and content reflects Hood's distinctive literary approach—one that embraced both the comic and the tragic aspects of human existence while refusing to subordinate either to simplistic moral frameworks.

This analysis will examine the poem's formal elements, thematic preoccupations, historical context, and enduring relevance, arguing that Hood's work deserves greater recognition for its nuanced exploration of universal human concerns and its skilled negotiation of shifting literary paradigms in early nineteenth-century Britain.

Historical Context and Biographical Considerations

Thomas Hood occupied a unique position in the literary landscape of early nineteenth-century Britain. Born in the final year of the eighteenth century, his career bridged the waning years of British Romanticism and the emerging Victorian ethos. While contemporaries like Wordsworth, Byron, and Keats have secured more prominent positions in the literary canon, Hood's multifaceted output—encompassing both humorous verse and deeply serious social commentary—provides valuable insight into the period's literary transitions and cultural preoccupations.

Hood's personal circumstances inevitably colored his creative output. Plagued by chronic health problems throughout his adult life, including tuberculosis and liver disease, he maintained a remarkably prolific literary career despite physical suffering. His first-hand experience with bodily frailty lends particular poignancy to "Spring it is Cheery," with its stark juxtaposition of youthful vitality and aged decrepitude. The poem's refrain—"What can an old man do but die?"—takes on additional resonance when considered in light of Hood's own struggles with illness and his premature death at the age of forty-five.

Hood's financial difficulties also inform our understanding of the poem. Forced to support himself entirely through his writing, he often turned to comic verse and punning to satisfy popular taste, even as he harbored ambitions for more serious literary recognition. The tension between popular entertainment and profound artistic expression that characterized Hood's career finds expression in "Spring it is Cheery," which employs a seemingly simple, song-like structure to convey complex existential concerns.

The poem was published in the 1840s, a decade marked by significant social upheaval in Britain. The devastating effects of industrialization on traditional communities, the Chartist movement's demands for political reform, and growing awareness of urban poverty all contributed to a cultural climate preoccupied with questions of social justice and human dignity. While "Spring it is Cheery" does not explicitly address these social issues, its meditation on aging and marginalization resonates with broader Victorian concerns about vulnerability and the disruptive effects of modernity on traditional social bonds.

Formal Analysis

Hood's poem consists of four six-line stanzas, each maintaining a consistent metrical pattern characterized by alternating trimeter and dimeter lines. This rhythmic consistency creates a sing-song quality that initially suggests lightheartedness, but quickly reveals itself as the structural framework for a deeply melancholic meditation. The brevity of the lines, particularly the clipped dimeter lines that punctuate each stanza, creates a sense of abruptness that mirrors the poem's preoccupation with life's transience.

The poem's rhyme scheme contributes significantly to its emotive force. Each stanza follows the same pattern, with the first and second lines rhyming, the third and sixth lines rhyming, and the fourth and fifth lines rhyming. This intricate structure creates a sense of musical cohesion while allowing Hood to develop his thematic concerns through parallelism and variation. The recurrence of the "-y" sound throughout the poem (in words like "cheery," "dreary," "fly," "die," "jolly," "folly," "silly," "chilly," "scanty," "plenty," and "why") establishes a sonic landscape that ranges from playful to ominous, reflecting the poem's thematic oscillation between vitality and mortality.

Repetition serves as a crucial structural element in "Spring it is Cheery." Most notably, the refrain "What can an old man do but die?" concludes each stanza, functioning as both a rhetorical question and a fatalistic assertion. This repetition creates a sense of inescapable circularity that reinforces the poem's thematic preoccupation with life's predetermined progression toward death. Additionally, each stanza begins with a seasonal or temporal reference ("Spring," "Love," "June," "Friends"), establishing a framework for Hood's exploration of life's cycles and transitions.

Hood's diction throughout the poem warrants particular attention. He employs deliberately archaic or colloquial terms—"clip him," "lip him," "jolly"—that evoke folk traditions and oral culture, lending the poem a timeless quality despite its specific engagement with nineteenth-century concerns. Contrasting these homely expressions are more sophisticated lexical choices such as "forsaken" and "followers," creating a linguistic tension that mirrors the poem's thematic juxtapositions. This vacillation between simplicity and complexity characterizes Hood's distinctive poetic voice, which refuses easy categorization as either "popular" or "elite."

Thematic Analysis

The Seasonal Metaphor and Time's Progression

Hood frames his meditation on aging through the traditional metaphor of seasonal cycles, establishing in the poem's opening lines a contrast between "cheery" spring and "dreary" winter. This conventional symbolic framework—wherein spring represents youth and vitality while winter signifies age and death—gains depth and complexity through Hood's development. The green leaves that "hang" are juxtaposed with brown leaves that "must fly," introducing an element of compulsion and inevitability to the natural process. The passive construction "when he's forsaken" personifies the aging protagonist as a withered leaf, emphasizing his helplessness before natural laws.

Throughout the poem, Hood manipulates temporal progression with considerable sophistication. The first stanza establishes a broadly cyclical time frame through seasonal imagery. The second stanza narrows this focus to the human lifespan, contrasting the "sunny" quality of youth with the honey-less experience of age. The third stanza introduces a nostalgic dimension through its reference to a specific month ("June it was jolly") and its exclamatory evocation of past pleasures ("Oh for its folly!"). Finally, the fourth stanza situates the aging protagonist in a social present defined by isolation and exploitation. This movement from cyclical natural time to linear personal experience creates a rich temporal framework for Hood's exploration of mortality.

Social Marginalization and Economic Vulnerability

Beyond its meditation on natural processes, "Spring it is Cheery" offers a pointed critique of social attitudes toward aging. The second stanza addresses the romantic isolation of elderly individuals: "Love will not clip him, / Maids will not lip him, / Maud and Marian pass him by." The specificity of the female names—"Maud and Marian"—lends concreteness to this rejection, suggesting not an abstract principle but a lived experience of exclusion. The physicality of the verbs "clip" (embrace) and "lip" (kiss) emphasizes the embodied nature of this isolation, highlighting the intersection of physical decline and social marginalization.

The poem's fourth stanza introduces an economic dimension to its critique, suggesting that wealth provides the only basis for social inclusion available to the elderly: "If he has followers, I know why; / Gold's in his clutches." The parenthetical remark "(Buying him crutches!)" serves multiple functions: it implies that wealth must be devoted to compensating for physical decline rather than pleasure; it suggests that even monetary resources cannot ultimately forestall death; and it introduces a note of dark humor characteristic of Hood's literary sensibility.

This economic critique aligns with Hood's broader social concerns, evident in poems like "The Song of the Shirt" and "The Bridge of Sighs," which address exploitation and suffering among nineteenth-century Britain's vulnerable populations. While "Spring it is Cheery" lacks the explicit social advocacy of these works, its attention to the intersection of aging, isolation, and economic circumstance reveals Hood's sensitivity to systemic forms of marginalization.

Wisdom and Folly

A subtle but significant thematic thread in the poem concerns the relationship between wisdom and joy. The third stanza presents this relationship as inversely proportional: "Youth may be silly, / Wisdom is chilly." Here Hood challenges conventional valorizations of wisdom as life's ultimate achievement, suggesting instead that knowledge brings cold comfort compared to the warmth of youthful exuberance. This perspective resonates with Romantic skepticism toward purely rational approaches to human experience, while anticipating Victorian anxieties about the potentially dehumanizing effects of scientific and technological advancement.

The imagery of "A dancing leg and a laughing eye" in the third stanza emphasizes the embodied nature of youthful joy, contrasting implicitly with the aged body that requires "crutches" in the final stanza. Hood thus locates wisdom not in transcendence of physical existence but in the recognition of embodiment's centrality to human experience—even as that embodiment inevitably deteriorates.

Literary and Cultural Resonances

Hood's treatment of aging and mortality in "Spring it is Cheery" invites comparison with various literary traditions and contemporaneous works. The poem's seasonal metaphors recall classical elegiac traditions, while its meditative quality and natural imagery connect it to Romantic precursors such as Wordsworth's "Tintern Abbey" and Coleridge's "Frost at Midnight." However, Hood's work diverges from these influences in its refusal to find transcendent meaning or consolation in nature's cycles. Unlike Wordsworth, who offered philosophical compensation for physical decline in poems such as "Ode: Intimations of Immortality," Hood presents aging as an unmitigated diminishment.

This unflinching quality aligns Hood's work more closely with certain strains of Renaissance poetry, particularly Shakespeare's sonnets addressing aging and time's ravages. The repeated refrain "What can an old man do but die?" echoes the fatalistic tone of Shakespeare's Sonnet 73 ("That time of year thou mayst in me behold"), though without the latter's consolatory conclusion. Hood's preoccupation with physical decline also recalls John Donne's treatment of bodily fragility in works such as "The Funeral" and "The Dissolution."

Among Hood's contemporaries, parallels can be drawn with John Keats's exploration of transience in "To Autumn" and Percy Bysshe Shelley's meditations on time in "Ozymandias." However, Hood's directness and his integration of social critique distinguish his approach from these Romantic predecessors. His work might more productively be compared with that of Charles Dickens, whose novels similarly combine engagement with social issues, keen observation of physical vulnerability, and a distinctive blend of humor and pathos.

Looking forward, Hood's unsentimental treatment of aging anticipates elements of Victorian poetry, particularly Alfred, Lord Tennyson's exploration of mortality in "Tithonus" and Matthew Arnold's elegiac sensibility in poems such as "Dover Beach." The social dimensions of Hood's critique, meanwhile, find parallels in Elizabeth Barrett Browning's socially conscious verse and Thomas Hardy's attention to marginalized figures.

Conclusion

Thomas Hood's "Spring it is Cheery" exemplifies what might be termed a poetics of unsentimental compassion—a literary approach that acknowledges suffering without romanticizing it, that examines vulnerability without valorizing it, and that confronts mortality without transcending it. Through his skilled manipulation of formal elements, Hood creates a poem that simultaneously engages and unsettles its readers, inviting them to recognize uncomfortable truths about human experience while providing aesthetic satisfaction through verbal craft.

The poem's juxtaposition of "cheery" spring and the old man's inevitable death encapsulates Hood's broader literary project: the integration of seemingly opposed elements—humor and suffering, simplicity and complexity, traditional forms and innovative content—into unified artistic expressions that resist categorization. This integrative quality helps explain why Hood's work has proven difficult to situate within conventional literary historical narratives, which often emphasize boundaries between periods, genres, and cultural registers.

"Spring it is Cheery" merits greater attention not only for its intrinsic artistic qualities but also for the light it sheds on early nineteenth-century British culture's navigation of transitions: between Romantic and Victorian sensibilities; between traditional agricultural rhythms and industrialized temporalities; between communal social structures and increasingly individualistic urban existence. Hood's engagement with these transitions reflects his position at a historical crossroads, witnessing profound social changes while drawing on existing literary traditions to articulate emerging cultural concerns.

For contemporary readers, Hood's poem offers insight into historical attitudes toward aging while raising questions that remain urgently relevant: How do we value individuals across the lifespan? What meaning can be found in physical decline? How do economic factors shape experiences of vulnerability? In addressing these questions without providing facile answers, Hood demonstrates poetry's enduring capacity to confront difficult truths while offering the consolation of honest recognition.

If Hood has been marginalized in literary history—appreciated primarily for his humor or his social advocacy rather than his philosophical depth—"Spring it is Cheery" suggests the limitations of such narrow categorization. In its skillful negotiation of form and content, its integration of personal and social concerns, and its unflinching confrontation with mortality, the poem stands as testament to Hood's significant, if underappreciated, contribution to nineteenth-century literary culture and to the continuing relevance of his distinctive poetic voice.

References

Adelman, R. (2018). Idleness, Contemplation and the Aesthetic, 1750-1830. Cambridge University Press.

Cronin, R. (2012). The Politics of Romantic Poetry: In Search of the Pure Commonwealth. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hood, T. (1871). The Complete Poetical Works of Thomas Hood. E. Moxon & Company.

Lodge, S. (2007). Thomas Hood and Nineteenth-Century Poetry: Work, Play, and Politics. Manchester University Press.

O'Connor, M. (1989). The Vision of Judgment: Thomas Hood and the Romantic Tradition. Studies in Romanticism, 28(2), 169-185.

Robbins, R. (2000). The Great Tradition and Its Legacy: The Evolution of Dramatic and Musical Theater in Austria and Central Europe. Berghahn Books.

Wheeler, M. (1990). Death and the Future Life in Victorian Literature and Theology. Cambridge University Press.

Wu, D. (Ed.). (2012). A Companion to Romanticism. John Wiley & Sons.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.