Praise Song to the Elephant

Credo Mutwa

1921 to 2020

Be angry, angry one!

Be angry at the clouds and the mountains!

Be angry at the sky and the rivers!

Be angry at the sea and the trees!

You are the elephant!

You, whose loud trumpeting heralded the birth of the world

You, whose last trumpeting will herald the end of the world we know

Be angry, great elephant

You, who are hunted by those who fear you

You, who are sought by those who should respect you

You, whose tusks are the ploughs that showed our grandmothers the way

You, whose great feet pounded the earth, the hard earth into powder in ancient times, so that green things might grow

Be angry, elephant, shout at the gods of Africa

Be angry, elephant, shout at the grey ghosts of our forefathers

Be angry, elephant, and shout at the people of modern days who do not do anything to shield you from the murderer and the thief.

Credo Mutwa's Praise Song to the Elephant

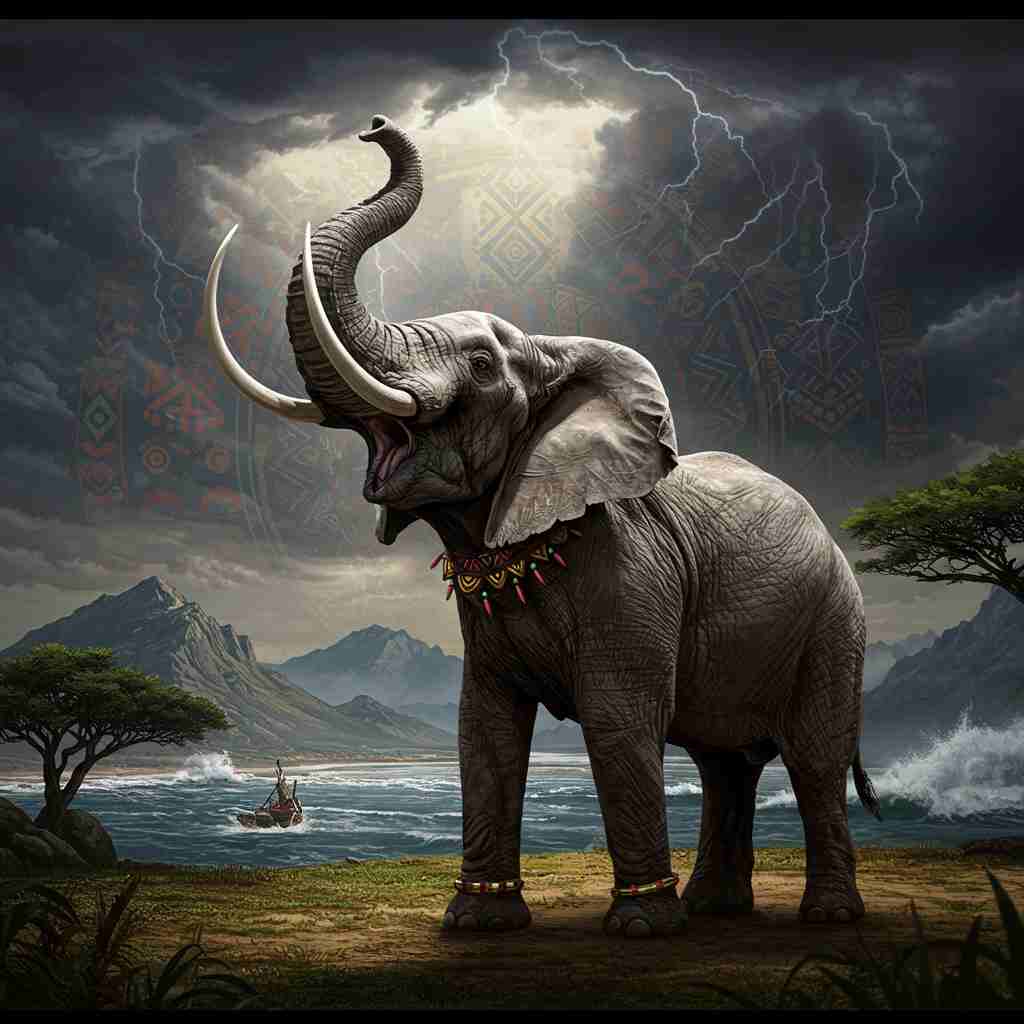

Credo Mutwa’s Praise Song to the Elephant is a powerful incantation that blends reverence, ecological urgency, and cultural lament. The poem, rooted in African oral traditions, serves both as a celebration of the elephant’s mythic grandeur and as a searing indictment of human exploitation. Mutwa, a renowned Zulu sangoma (traditional healer) and storyteller, crafts this piece with a prophetic tone, invoking the elephant as a symbol of ancient wisdom, ecological balance, and spiritual authority. The poem’s rhythmic intensity and imperative commands create a sense of ritualistic urgency, positioning the elephant not merely as an animal but as a divine force whose fate is intertwined with humanity’s moral and environmental decay.

This analysis will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its thematic concerns (including ecological destruction, colonialism, and spiritual disconnection), and its emotional resonance. By situating the poem within Mutwa’s broader body of work and within African literary traditions, we can better appreciate its significance as both a cultural artifact and a contemporary environmental plea.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully grasp the depth of Praise Song to the Elephant, one must understand the elephant’s symbolic weight in African cosmology. Across many African cultures, the elephant is revered as a totem of strength, wisdom, and memory. In some traditions, it is seen as a mediator between the human and divine realms, a creature whose presence signifies both earthly power and spiritual guidance. Mutwa’s invocation of the elephant aligns with these beliefs, but he also subverts them by portraying the elephant not as a passive deity but as an enraged force—one that has been betrayed by humanity.

The poem also reflects the brutal history of elephant poaching, a crisis exacerbated by European colonialism and the global ivory trade. Africa’s elephants were hunted to near extinction in the 19th and 20th centuries, their tusks commodified for Western markets. Mutwa’s call for the elephant to "be angry" is thus not merely metaphorical but a direct response to this historical violence. His reference to "the murderer and the thief" implicates both colonial exploiters and contemporary poachers, framing ecological destruction as an ongoing legacy of greed and disrespect.

Furthermore, the poem engages with African oral traditions, particularly the praise song (or izibongo in Zulu culture), a poetic form used to honor leaders, ancestors, and natural forces. By adopting this form, Mutwa elevates the elephant to the status of a sacred being deserving of reverence, while also using the praise song’s rhetorical power to provoke moral awakening.

Literary Devices and Structure

Mutwa employs a series of commanding repetitions—"Be angry"—to create a hypnotic, incantatory rhythm. This repetition mimics ceremonial invocations, reinforcing the poem’s ritualistic quality. The imperative mood transforms the poem into a summoning, as though the speaker is attempting to rouse not just the elephant but the collective conscience of humanity.

The poem’s imagery is both mythic and visceral. The elephant’s "loud trumpeting" is said to have heralded "the birth of the world" and will signal "the end of the world we know," positioning the creature as a cosmic force. This aligns with creation myths in which the elephant is a primordial being, a shaper of landscapes. The lines—

"You, whose tusks are the ploughs that showed our grandmothers the way

You, whose great feet pounded the earth, the hard earth into powder in ancient times, so that green things might grow"

—evoke the elephant’s role in ecological and agricultural history, suggesting that its very existence sustains life. The juxtaposition of this generative power with its current persecution deepens the poem’s tragedy.

Mutwa also employs personification and apostrophe, addressing the elephant directly as though it were a deity or ancestral spirit. This technique blurs the line between animal and myth, reinforcing the idea that the elephant is not just a victim of human cruelty but a witness to it—one that may yet retaliate. The invocation of "the gods of Africa" and "the grey ghosts of our forefathers" further situates the elephant within a spiritual framework, suggesting that its suffering is a sacrilege that offends both the divine and the ancestral.

Themes and Philosophical Underpinnings

1. Ecological Destruction and Human Betrayal

The central theme of Praise Song to the Elephant is the catastrophic impact of human exploitation on nature. The poem’s anger is directed not only at poachers but at all who fail to act—"the people of modern days who do not do anything to shield you." This indictment extends beyond individual culprits to systemic apathy, critiquing modernity’s alienation from nature.

The elephant, in this context, becomes a symbol of the natural world’s silent suffering. Its "last trumpeting" heralding the "end of the world" suggests that ecological collapse is not just an environmental issue but an existential one—the destruction of the elephant signifies the unraveling of creation itself.

2. Colonialism and Cultural Erasure

Mutwa’s work often addresses the scars of colonialism, and this poem is no exception. The elephant’s tusks, once "ploughs that showed our grandmothers the way," are now commodities, stripped of their cultural and spiritual significance. This imagery reflects how colonialism transformed sacred elements of African life into raw materials for European profit.

The call for the elephant to "shout at the grey ghosts of our forefathers" suggests a rupture between past and present—a betrayal of ancestral wisdom. The "grey ghosts" may symbolize the lingering trauma of colonialism, haunting a people who have forgotten how to protect their own land and traditions.

3. Spiritual Disconnection and the Need for Reawakening

The poem’s ritualistic tone implies that the solution to ecological and cultural crisis is not merely political but spiritual. The elephant’s anger is not just an emotion but a divine judgment, a call for humanity to realign itself with sacred duty.

By invoking African gods and ancestors, Mutwa suggests that environmental justice is inseparable from cultural and spiritual revival. The poem thus functions as both a lament and a rallying cry—a demand for reconnection with the values that once ensured harmony between humans and nature.

Comparative Readings and Broader Literary Connections

Mutwa’s poem resonates with other works of African environmental literature, such as Wole Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman, which also explores the consequences of disrupting sacred natural orders. Similarly, it echoes the eco-poetry of South African writers like Mongane Wally Serote, whose works mourn the degradation of land and culture under apartheid.

Globally, the poem aligns with ecocritical poetry that personifies nature as a wounded deity, such as Pablo Neruda’s Ode to the Sea or Robinson Jeffers’ Hurt Hawks. However, Mutwa’s work is distinct in its grounding in African spirituality, offering a decolonial perspective that centers indigenous cosmologies rather than Western environmentalism.

Emotional Impact and Contemporary Relevance

The poem’s raw urgency makes it emotionally gripping. The repetition of "Be angry" builds a crescendo of desperation, as though the speaker is trying to awaken a slumbering giant before it is too late. The final lines—

"shout at the people of modern days who do not

do anything to shield you from the murderer and the thief."

—land with accusatory force, implicating the reader in the elephant’s plight. This technique ensures that the poem is not just observed but felt, compelling the audience to confront their own complicity in ecological violence.

In today’s context of climate crisis and mass extinction, Praise Song to the Elephant is tragically relevant. The ongoing poaching crisis, habitat destruction, and climate change make Mutwa’s words prophetic. The poem challenges us to consider: if the elephant—a creature of such mythic importance—can be reduced to a commodity, what does that say about humanity’s future?

Conclusion

Credo Mutwa’s Praise Song to the Elephant is a masterful fusion of myth, lament, and protest. Through its incantatory rhythm, vivid imagery, and spiritual depth, the poem elevates the elephant from a mere animal to a cosmic force whose fate mirrors our own. It is a call to remember—to reclaim the reverence for nature that modernity has eroded.

In an era of environmental collapse, Mutwa’s words resonate with terrifying clarity. The elephant’s anger is not just its own; it is the anger of the earth itself, betrayed by those who should have been its stewards. The poem’s power lies in its ability to transform grief into a demand for action, ensuring that the elephant’s trumpeting is not just a herald of the end, but perhaps, if we listen, a call to a new beginning.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.