Orion

Charles Tennyson Turner

1808 to 1879

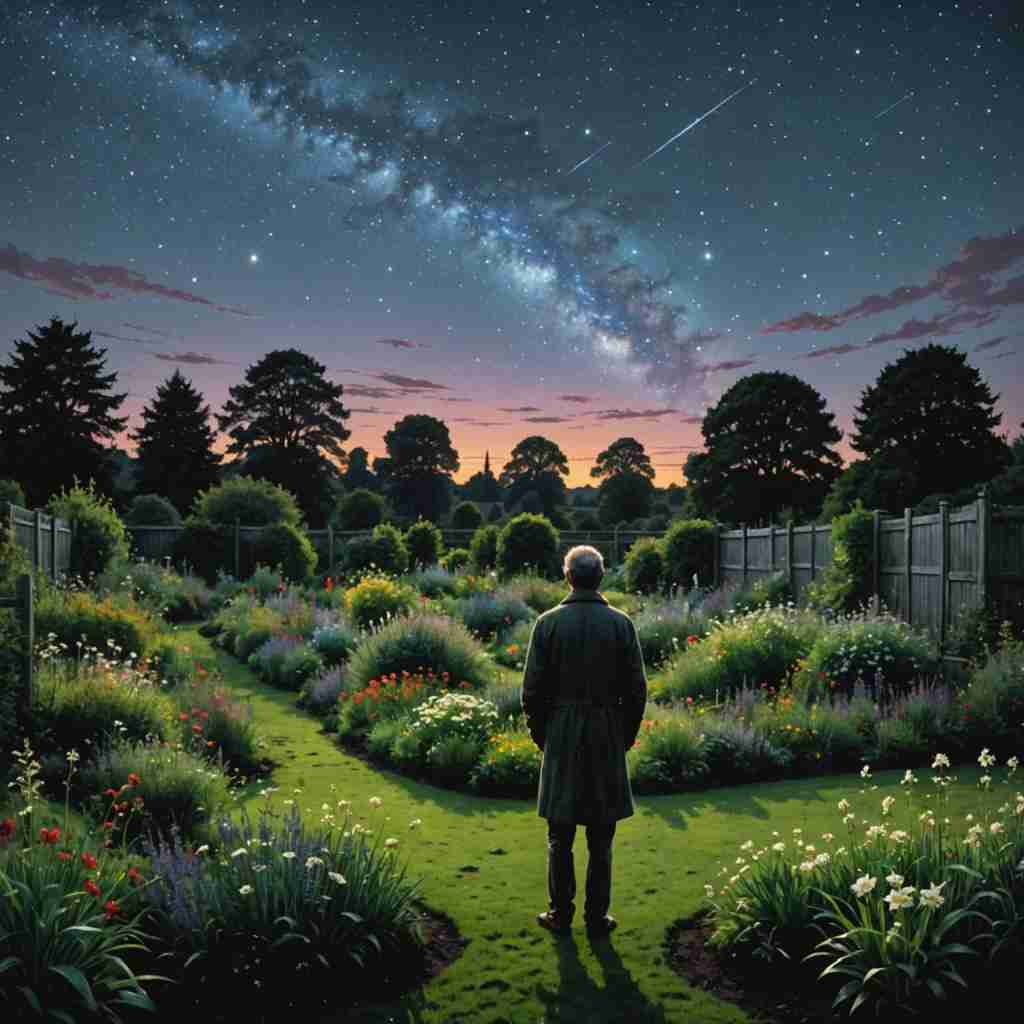

How oft I've watched thee from the garden croft,

In silence, when the busy day was done,

Shining with wondrous brilliancy aloft,

And flickering like a casement 'gainst the sun:

I've seen thee soar from out some snowy cloud,

Which held the frozen breath of land and sea,

Yet broke and severed as the wind grew loud —

But earth-bound winds could not dismember thee.

Nor shake thy frame of jewels; I have guessed

At thy strange shape and function, haply felt

The charm of that old myth about thy belt

And sword; but, most, my spirit was possest

By His great presence, Who is never far

From his light-bearers, whether man or star.

Charles Tennyson Turner's Orion

Charles Tennyson Turner's sonnet "Orion" represents a masterful confluence of astronomical observation, mythological allusion, and spiritual contemplation. Published in the mid-nineteenth century, this compact yet profound poem exemplifies the Victorian fascination with both scientific advancement and religious devotion. Turner, often overshadowed by his more famous brother Alfred, Lord Tennyson, demonstrates in "Orion" his own poetic gifts—a keen eye for natural phenomena combined with a contemplative soul seeking transcendent meaning in the observable universe.

This analysis will explore how Turner transforms the familiar astronomical constellation into a multi-layered poetic symbol. Through careful examination of the sonnet's formal qualities, imagery, and thematic resonances, we shall see how Turner bridges the Romantic tradition's reverence for nature with Victorian religious sensibilities. The poem ultimately reveals a worldview in which scientific observation and spiritual revelation are not opposing forces but complementary paths to understanding humanity's place in the cosmos.

Historical and Literary Context

Charles Tennyson Turner (1808-1879) wrote during a period of significant intellectual and social transformation in England. The Victorian era witnessed unprecedented scientific discoveries that challenged traditional religious narratives, while simultaneously experiencing religious revivals and theological debates. The publication of Charles Darwin's "On the Origin of Species" in 1859 dramatically intensified questions about the relationship between science and faith that had been brewing throughout the century.

Turner's poetic career developed against this backdrop of intellectual ferment. Having taken holy orders in 1832, he served as a country vicar for most of his adult life, and his religious convictions deeply informed his poetic vision. Like many educated Victorians, however, Turner did not see scientific inquiry as inherently threatening to faith. Rather, his poetry often attempts to reconcile careful observation of the natural world with religious devotion, finding evidence of divine design in nature's patterns and beauty.

The sonnet tradition in which Turner worked was particularly suited to this contemplative approach. The form's structural movement from observation to reflection allowed poets to build toward moments of insight or revelation. Turner published several volumes of sonnets throughout his career, perfecting a style that Alfred Tennyson described as possessing "the utmost perfection of which this species of composition is capable." "Orion" exemplifies this craftsmanship, moving from precise astronomical observation to spiritual epiphany within its fourteen lines.

Formal Analysis

"Orion" follows the Petrarchan sonnet form with its characteristic octave-sestet structure, though Turner modifies the traditional rhyme scheme slightly. The octave (first eight lines) establishes the speaker's observation of the constellation, while the sestet (final six lines) shifts to contemplation of its mythological and spiritual significance. This formal division mirrors the poem's thematic movement from external observation to internal reflection.

The poem's meter is regular iambic pentameter, creating a measured, contemplative rhythm appropriate to nighttime stargazing. Turner occasionally introduces metrical variations that correspond with shifts in thought or emphasis. For instance, the strong stress on "soar" in line five ("I've seen thee soar from out some snowy cloud") accentuates the upward movement described, while the caesura after "shape and function" in line ten creates a meditative pause as the speaker transitions from scientific curiosity to mythological and religious contemplation.

Turner's diction balances scientific precision with poetic elevation. Words like "brilliancy," "flickering," and "dismember" provide concrete descriptive accuracy, while "jewels," "charm," and "spirit" introduce more abstract, contemplative elements. This linguistic range reflects the poem's movement between empirical observation and spiritual intuition.

Imagery and Symbolism

The poem begins with the speaker watching Orion "from the garden croft," establishing both an intimate, domestic setting and a suggestion of Eden-like contemplation. The "silence" and timing ("when the busy day was done") create a mood of tranquility conducive to both astronomical observation and spiritual reflection. Throughout the octave, Turner develops vivid visual imagery that captures both the scientific reality of the constellation and its numinous quality.

The comparison of Orion's stars to "a casement 'gainst the sun" in line four is particularly striking. This simile compares the twinkling of stars to sunlight reflecting off windowpanes, inverting the usual relationship between solar and stellar light. This comparison also introduces architectural imagery that subtly suggests divine design—the heavens as a constructed dwelling with windows looking out (or in).

Turner's portrayal of Orion emerging from clouds in lines five through eight develops a dynamic relationship between the terrestrial and celestial realms. The clouds hold "the frozen breath of land and sea," connecting earth's atmosphere to the human act of breathing, while their breaking and severing under wind creates dramatic tension. Significantly, while earthly elements change and disperse, Orion remains constant, unaffected by "earth-bound winds." This contrast establishes the constellation's permanence and transcendence relative to terrestrial phenomena.

The "frame of jewels" in line nine transforms astronomical bodies into precious stones, suggesting both material value and divine craftsmanship. This imagery prepares for the mythological reference to Orion's "belt and sword" in lines eleven and twelve, objects that identify the constellation's distinctive shape while evoking the Greek hunter of myth. The word "charm" in this context carries double significance—both the emotional appeal of the story and a suggestion of enchantment or magical power.

Thematic Analysis

Scientific Observation and Wonder

Turner's poem begins in careful observation, positioning the speaker as an amateur astronomer studying the night sky with attention and regularity ("How oft I've watched thee"). This empirical foundation grounds the poem in the Victorian era's scientific mindset, with its emphasis on direct observation and natural phenomena. The speaker notices specific visual qualities of the constellation—its brilliance, its flickering, its emergence from clouds—demonstrating attentiveness to astronomical details.

Yet this observation immediately generates wonder rather than mere cataloging of facts. The constellation's "wondrous brilliancy" suggests that scientific observation leads naturally to aesthetic appreciation and even a sense of the marvelous. By comparing Orion to "a casement 'gainst the sun," Turner makes the familiar strange and the distant intimate, recreating the sense of wonder that astronomical observation can produce.

The speaker acknowledges intellectual curiosity about the constellation when he mentions having "guessed at thy strange shape and function" (lines 9-10). This phrasing suggests both scientific hypothesis and the limits of human understanding—the "guessing" implies that complete knowledge remains elusive. This humility before the mysteries of the cosmos aligns with Victorian scientific thought at its most philosophical, which often acknowledged the boundaries of human comprehension.

Mythology and Cultural Memory

The sestet introduces mythological dimensions, as the speaker contemplates "that old myth about thy belt and sword" (lines 11-12). This reference to the Greek legend of Orion the hunter acknowledges how cultural narratives shape human understanding of natural phenomena. By describing the myth's influence as a "charm," Turner suggests that such stories possess emotional and imaginative power beyond mere explanation.

The word "haply" (line 10) indicates that the speaker's engagement with myth is tentative or occasional rather than systematic. This casual relationship to mythology reflects the Victorian period's complex relationship with classical traditions—acknowledging their cultural importance while prioritizing Christian frameworks. The mythological reference functions as an intermediate step between scientific observation and religious revelation, bridging ancient and modern ways of knowing.

Turner's phrase "that old myth" creates temporal distance, positioning mythology as a relic of the past rather than a living truth. Yet the speaker acknowledges having "felt the charm," suggesting that mythological explanations retain emotional resonance even in an age of scientific understanding. This ambivalence toward myth—recognizing its power while maintaining critical distance—characterizes the Victorian intellectual approach to pre-Christian traditions.

Divine Presence and Religious Faith

The poem culminates in an explicitly religious insight, as the speaker declares that "most, my spirit was possest / By His great presence, Who is never far / From his light-bearers, whether man or star" (lines 12-14). This revelation represents the poem's deepest layer of meaning, suggesting that both scientific observation and mythological appreciation ultimately lead to awareness of divine presence in the cosmos.

The capitalization of "Who" and "His" identifies the presence as the Christian God, while the possessive relationship ("His light-bearers") establishes both Orion and humans as created beings with a divine purpose. By linking stars and humans as fellow "light-bearers," Turner suggests a profound connection between astronomical bodies and human souls—both reflect divine light and serve as evidence of God's creative power.

The phrase "never far" emphasizes divine immanence rather than transcendence, suggesting that God's presence permeates the created world rather than residing solely beyond it. This theological perspective aligns with certain strands of Victorian Christianity that sought to recognize divine presence within nature rather than opposing natural and supernatural realms.

The word "possest" carries spiritual connotations of being filled or overtaken by divine influence. This language of spiritual possession suggests that the ultimate response to natural beauty is not merely intellectual appreciation but spiritual transformation—allowing oneself to be filled with awareness of divine presence.

Literary and Philosophical Influences

Turner's approach to nature and divinity in "Orion" reflects several important literary and philosophical traditions. The sonnet's movement from observation to insight follows Romantic patterns of nature poetry, particularly as developed by Wordsworth, whose influence on Victorian poetry remained strong. Like Wordsworth, Turner finds spiritual significance in attentive observation of natural phenomena, though his explicitly Christian framework distinguishes him from Romantic pantheistic tendencies.

The poem also engages with the natural theology tradition, which sought evidence of divine design and purpose in the natural world. William Paley's "Natural Theology" (1802) had articulated the argument from design that remained influential throughout the nineteenth century, and Turner's portrayal of the constellation as a "frame of jewels" suggests similar appreciation of apparent order and beauty in the cosmos as evidence of divine craftsmanship.

The integration of scientific observation, classical reference, and Christian revelation in "Orion" also recalls Coleridgean ideals of the reconciliation of seemingly disparate modes of understanding. Turner suggests that scientific, cultural, and religious ways of knowing are complementary rather than contradictory—each offers partial insight into the meaning of celestial phenomena.

Comparative Perspectives

Turner's treatment of celestial bodies as manifestations of divine presence bears comparison with Gerard Manley Hopkins' nature sonnets, though Hopkins would develop a more linguistically innovative approach to similar themes later in the Victorian period. Both poets share a sacramental vision that finds evidence of divine presence in natural phenomena, though Turner's style remains more restrained and classical than Hopkins' experimental "sprung rhythm."

The astronomical focus of "Orion" also invites comparison with Tennyson's more cosmologically expansive poems like "Locksley Hall" and parts of "In Memoriam," which grapple with the implications of nineteenth-century astronomical discoveries. While Alfred Tennyson often expresses anxiety about the vastness of cosmic time and space, Charles Tennyson Turner finds reassurance in the divine presence that permeates both heavenly bodies and human observers.

Turner's integration of mythological reference with religious contemplation also recalls elements of John Keats' treatment of classical material, though without Keats' sensual emphasis. For Turner, mythology serves primarily as a cultural stepping-stone toward religious truth rather than as an alternative system of meaning.

Biographical Connections

Charles Tennyson Turner's career as a country vicar undoubtedly influenced his approach to nature and spirituality in "Orion." The poem's opening setting—watching stars "from the garden croft"—reflects the rural environment in which Turner spent most of his life. This positioning of the speaker in a domestic rural space while observing cosmic phenomena captures the integration of ordinary life and spiritual contemplation that characterized Turner's dual vocation as priest and poet.

Turner's relationship with his more famous brother Alfred also provides context for understanding "Orion." While Alfred Tennyson's poetry often expressed doubt and spiritual questioning, Charles generally maintained a more confident religious outlook. "Orion" exemplifies this faith in divine presence and purpose, offering a more settled theological perspective than Alfred's more tormented metaphysical explorations in poems like "In Memoriam."

Emotional and Psychological Dimensions

Beyond its theological and philosophical dimensions, "Orion" captures a profound psychological experience—the sense of connection and significance that humans can feel when contemplating the night sky. The poem traces an emotional journey from curiosity through wonder to spiritual communion, portraying how astronomical observation can transcend purely intellectual engagement to become an emotionally and spiritually transformative experience.

The phrase "my spirit was possest" suggests a surrendering of self to something greater—an experience of transcendence that dissolves boundaries between observer and observed, human and cosmos, natural and supernatural. This emotional trajectory from observation to communion represents a fundamentally religious pattern of experience, even as it begins in scientific observation.

Conclusion

Charles Tennyson Turner's "Orion" achieves remarkable depth within its compact sonnet form, weaving together astronomical observation, mythological allusion, and religious revelation. The poem exemplifies Victorian attempts to integrate scientific knowledge with religious faith, finding evidence of divine presence in the very natural phenomena that contemporary science was explaining in mechanical terms.

The sonnet's formal movement from octave to sestet mirrors its conceptual progression from observation to insight, while its imagery builds from literal description to symbolic resonance. Turner's controlled diction and measured rhythm create a contemplative space in which scientific precision and spiritual intuition coexist and complement each other.

"Orion" ultimately suggests that complete understanding of the cosmos requires multiple modes of knowing—the empirical observation valued by science, the cultural narratives preserved in mythology, and the spiritual intuition cultivated by religion. In Turner's integrated vision, the constellation serves as both an astronomical phenomenon worthy of scientific attention and a divine "light-bearer" manifesting God's presence in the created universe.

This integration of different ways of knowing reflects a characteristic Victorian attempt to maintain spiritual meaning within an increasingly scientific worldview. Rather than retreating from scientific observation or rejecting religious frameworks, Turner demonstrates how careful attention to natural phenomena can lead to deeper spiritual awareness—how looking outward at the stars can ultimately turn the observer inward toward divine presence.

In our contemporary context, where science and religion are often positioned as antagonists, Turner's "Orion" offers a reminder of an alternative approach—one that values both empirical observation and spiritual insight, finding in the wonders of the cosmos evidence not only of natural processes but also of transcendent meaning and presence.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem analysis. This exercise is designed for classroom use.