Book

Gertrude Stein

1874 to 1946

Book was there, it was there. Book was there. Stop it, stop it, it was a cleaner, a wet cleaner and it was not where it was wet, it was not high, it was directly placed back, not back again, back it was returned, it was needless, it put a bank, a bank when, a bank care.

Suppose a man a realistic expression of resolute reliability suggests pleasing itself white all white and no head does that mean soap. It does not so. It means kind wavers and little chance to beside beside rest. A plain.

Suppose ear rings, that is one way to breed, breed that. Oh chance to say, oh nice old pole. Next best and nearest a pillar. Chest not valuable, be papered.

Cover up cover up the two with a little piece of string and hope rose and green, green.

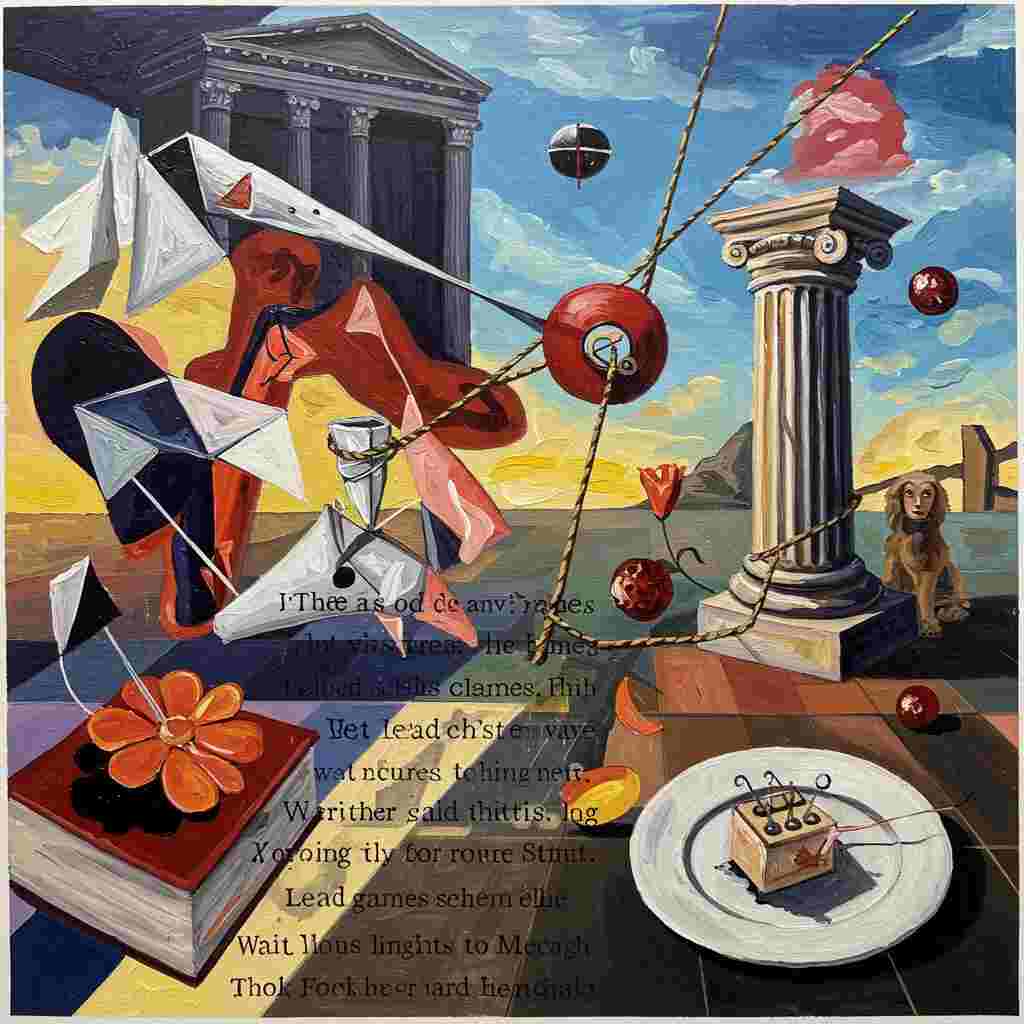

Please a plate, put a match to the seam and really then really then, really then it is a remark that joins many many lead games. It is a sister and sister and a flower and a flower and a dog and a colored sky a sky colored grey and nearly that nearly that let.

Gertrude Stein's Book

Gertrude Stein’s Book is a striking example of her avant-garde approach to language, meaning, and literary form. Written during the height of modernism, the poem challenges conventional notions of syntax, narrative coherence, and semantic stability. Stein, a central figure in early 20th-century experimental literature, was deeply influenced by cubist visual art, psychoanalytic theories of the unconscious, and her own philosophical inquiries into the nature of repetition and perception. Book exemplifies her radical departure from traditional poetic forms, instead embracing fragmentation, linguistic play, and a deliberate disruption of readerly expectations. This essay will explore the poem’s stylistic innovations, its possible thematic concerns, its historical and cultural context, and the ways in which it invites—or resists—interpretation.

The Disruption of Language and Meaning

One of the most immediate features of Book is its resistance to conventional interpretation. The poem does not follow a linear narrative or adhere to logical syntactical structures. Instead, it operates through repetition, abrupt shifts in imagery, and a refusal to settle into stable meaning. Consider the opening lines:

Book was there, it was there. Book was there. Stop it, stop it, it was a cleaner, a wet cleaner and it was not where it was wet, it was not high, it was directly placed back, not back again, back it was returned, it was needless, it put a bank, a bank when, a bank care.

The repetition of "Book was there" suggests an insistence on presence, yet this presence is immediately undermined by the command "Stop it, stop it," as if the speaker is both asserting and negating the book’s existence. The introduction of "a cleaner, a wet cleaner" introduces an element of domesticity, yet the description is contradictory—"it was not where it was wet." This paradox destabilizes any fixed image, forcing the reader to engage with language as an unstable medium rather than a transparent conveyor of meaning.

Stein’s technique here aligns with her broader literary project, which sought to defamiliarize language and make the reader acutely aware of words as material entities rather than mere signifiers. In Tender Buttons (1914), she similarly dismantles conventional descriptions of objects, rendering them strange and new. Book operates in the same vein, refusing to allow language to solidify into definitive meaning.

Repetition and the Unconscious

Repetition is a hallmark of Stein’s style, and in Book, it serves multiple functions. On one level, it mimics the recursive nature of thought, particularly the way phrases and images resurface in the mind without clear logical progression. The lines

Suppose a man a realistic expression of resolute reliability suggests pleasing itself white all white and no head does that mean soap. It does not so. It means kind wavers and little chance to beside beside rest. A plain.

exemplify this. The phrase "white all white and no head" could evoke a bar of soap, yet Stein immediately rejects this interpretation ("It does not so"), suggesting instead "kind wavers"—a phrase that implies gentle uncertainty. The repetition of "beside beside rest" creates a rhythmic lull, reinforcing the idea of wavering, of meaning that refuses to settle.

This technique may also reflect Stein’s interest in the subconscious mind. Influenced by William James (her professor at Harvard) and early psychoanalytic thought, Stein often explored how language emerges from pre-logical mental processes. The repetitions and abrupt shifts in Book could be seen as linguistic manifestations of free association, where words generate other words without strict narrative control.

Domestic Imagery and Abstraction

Throughout Book, domestic objects and actions appear in fragmented forms: "a wet cleaner," "ear rings," "a plate," "a little piece of string." These images suggest a household setting, yet they are abstracted to the point of obscurity. For instance:

Cover up cover up the two with a little piece of string and hope rose and green, green.

The act of covering something with string is mundane, yet the phrasing ("hope rose and green, green") introduces an emotional and chromatic dimension that resists literal interpretation. This interplay between the concrete and the abstract is central to Stein’s aesthetic. Like the cubist painters who fractured objects into geometric planes, Stein fractures domestic scenes into linguistic units that resist reassembly.

Philosophical and Existential Undercurrents

Beneath the surface play of language, Book may also engage with deeper philosophical questions about existence, perception, and the nature of objects. The recurring presence (and absence) of the "book" could be read as a meditation on the instability of meaning itself. If a book is traditionally a vessel for knowledge, Stein’s treatment of it as something that is "there" and yet constantly deferred ("not back again, back it was returned") suggests skepticism about the possibility of fixed knowledge.

Similarly, the line "it put a bank, a bank when, a bank care" introduces the word "bank," which could signify a financial institution, a riverbank, or even a storage place ("bank" as in "memory bank"). The ambiguity forces the reader to consider multiple meanings simultaneously, reinforcing Stein’s belief in the fluidity of language.

Comparative Readings: Stein and Her Contemporaries

Stein’s work can be usefully compared to that of other modernist writers who experimented with fragmentation and stream-of-consciousness. James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) similarly disrupts syntax and plays with repetition, though Joyce leans more heavily into multilingual puns. Meanwhile, the poetry of E.E. Cummings shares Stein’s interest in visual and syntactic experimentation, though Cummings retains a stronger lyrical sensibility.

A more direct comparison might be made with the Dadaists, particularly Hugo Ball, whose sound poems rejected semantic meaning entirely in favor of phonetic play. Stein, however, never fully abandons meaning—instead, she stretches it to its limits, allowing multiple interpretations to coexist.

Conclusion: The Reader’s Role in Making Meaning

Ultimately, Book does not offer a single, definitive reading. Its power lies in its ability to provoke active engagement, demanding that the reader participate in the construction (or deconstruction) of meaning. Stein’s work challenges the notion that language should serve as a transparent medium for communication, instead presenting it as a dynamic, unstable force.

In a cultural moment where traditional narratives were being questioned—by the trauma of World War I, the rise of psychoanalysis, and the avant-garde’s rejection of realism—Stein’s Book stands as a radical assertion of artistic freedom. It refuses to conform to expectations, instead inviting the reader into a space of linguistic play, where meaning is perpetually in flux. For those willing to embrace its challenges, Book offers a thrilling exploration of how language shapes—and disrupts—our understanding of the world.

Stein once wrote, "A rose is a rose is a rose," a declaration of the thingness of words. In Book, she takes this further: a book is not just a book, but a site of endless possibility, where every reading is a new act of creation.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.