Child of the Romans

Carl Sandburg

1878 to 1967

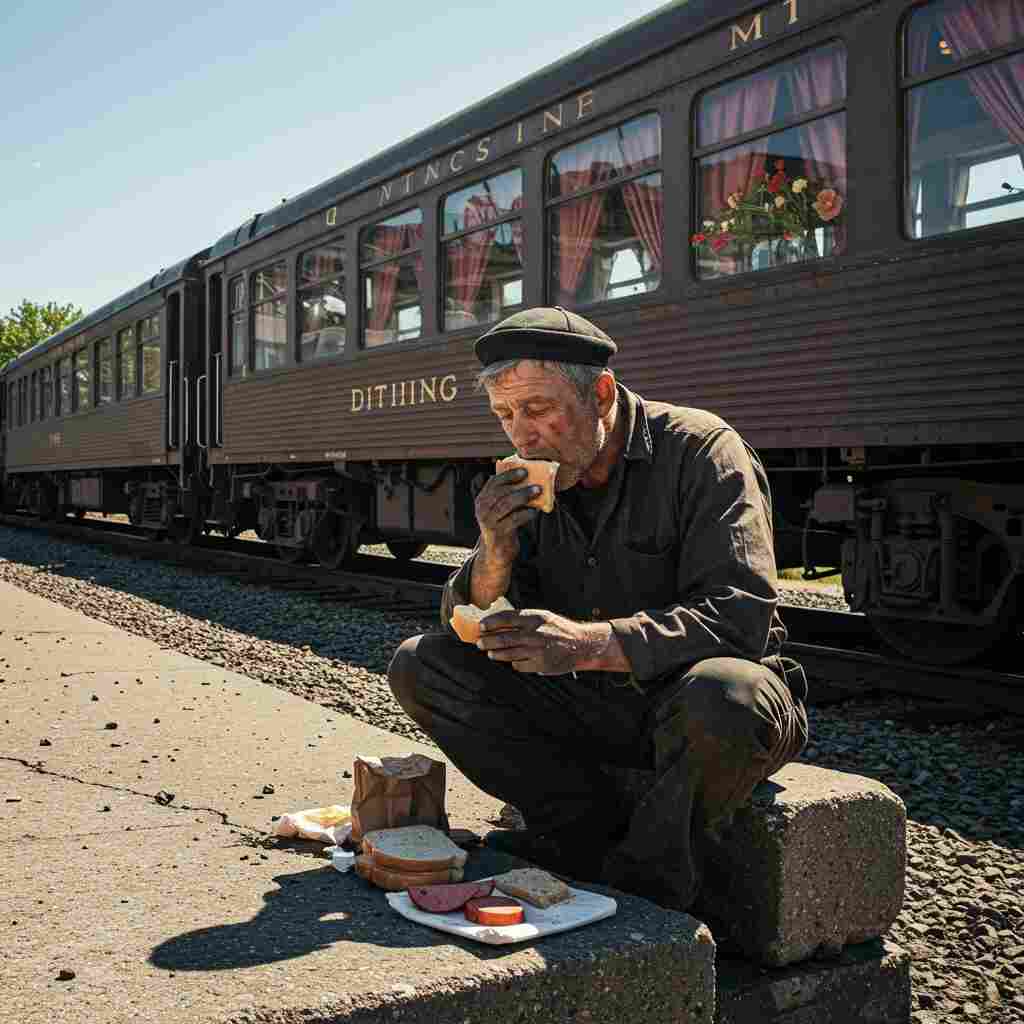

The dago shovelman sits by the railroad track

Eating a noon meal of bread and bologna

A train whirls by, and men and women at tables

Alive with red roses and yellow jonquils,

Eat steaks running with brown gravy,

Strawberries and cream, eclairs and coffee

The dago shovelman finishes the dry bread and bologna.

Washes it down with a dipper from the water-boy,

And goes back to the second half of a ten-hour day's work

Keeping the road-bed so the roses and jonquils

Shake hardly at all in the cut glass vases

Standing slender on the tables in the dining cars.

Carl Sandburg's Child of the Romans

Carl Sandburg’s "Child of the Romans" is a compact yet powerful poem that encapsulates the stark economic and social disparities of early 20th-century America. Through vivid imagery and stark contrasts, Sandburg critiques the exploitation of immigrant labor while highlighting the indifference of the privileged class. Written during a period of rapid industrialization and mass immigration, the poem reflects Sandburg’s broader socialist sympathies and his commitment to portraying the lives of the working class with dignity and realism. This analysis will explore the poem’s historical context, its use of literary devices, its central themes of labor and inequality, and its enduring emotional resonance.

Historical Context: Industrialization and Immigration

To fully appreciate "Child of the Romans," one must situate it within the early 20th-century American landscape—a time of immense industrial growth, labor struggles, and waves of European immigration. The poem’s reference to the "dago shovelman" (a now-offensive term for an Italian laborer) immediately signals the ethnic and class tensions of the era. Italian immigrants, like many others, were often relegated to grueling, low-wage jobs in railroads, construction, and factories. Sandburg, a journalist and poet deeply engaged with social issues, frequently wrote about the lives of workers, drawing attention to their exploitation while celebrating their resilience.

The railroad, a central symbol in the poem, was not only an engine of American progress but also a site of brutal labor conditions. The men who built and maintained the tracks—many of them immigrants—worked long hours for meager pay, their labor enabling the comfort and mobility of the wealthy. Sandburg’s depiction of the shovelman’s "ten-hour day’s work" underscores the physical toll of industrialization, while the luxurious dining car passengers remain oblivious to the labor that sustains their comfort.

Literary Devices: Contrast, Imagery, and Irony

Sandburg employs several key literary techniques to heighten the poem’s emotional and thematic impact. The most striking of these is contrast, which structures the entire poem. The shovelman’s humble meal of "bread and bologna" is juxtaposed against the lavish dining car spread of "steaks running with brown gravy, / Strawberries and cream, eclairs and coffee." This disparity is not merely culinary but symbolic—it represents the vast economic divide between laborers and the bourgeoisie.

The imagery is equally potent. The "red roses and yellow jonquils" in the dining car are delicate, almost frivolous, emphasizing the aesthetic pleasures enjoyed by the wealthy. Meanwhile, the shovelman’s sustenance is dry and utilitarian, washed down with a simple dipper of water. The flowers, kept steady by the laborer’s work, become ironic symbols of the unseen toil that upholds bourgeois comfort.

A subtle but devastating irony underlies the poem: the shovelman’s labor ensures that the dining car passengers experience no discomfort—their vases "shake hardly at all." The stability of their luxury depends entirely on his exhausting work, yet they remain unaware of his existence. This dynamic reflects Marx’s concept of alienated labor, where the worker’s efforts are invisible to those who benefit from them.

Themes: Labor, Inequality, and Invisibility

At its core, "Child of the Romans" is a meditation on labor and its invisibility. The shovelman’s work is essential, yet he is marginalized, both economically and socially. The title itself is significant—"Child of the Romans" evokes the grandeur of ancient Rome, subtly contrasting the dignity of the laborer’s heritage with his diminished status in industrial America. Sandburg suggests that the modern worker, though far removed from the glory of classical civilizations, is nonetheless a foundational figure in society.

The poem also explores economic inequality as an inherent feature of industrial capitalism. The dining car passengers indulge in excess, while the laborer barely subsists. There is no direct interaction between the two groups—they exist in parallel worlds, one of leisure and the other of relentless toil. This separation underscores the dehumanization of labor, where workers become mere instruments rather than individuals with their own needs and desires.

A third, more subtle theme is motion and stasis. The train "whirls by," suggesting speed and progress, yet the shovelman remains static, tied to his repetitive labor. The passengers move forward in comfort, while the worker is fixed in place, his labor cyclical and unending. This contrast critiques the myth of upward mobility, revealing how industrialization often entrenches rather than alleviates class divisions.

Emotional Impact: Dignity and Resignation

Despite its critique of social inequality, the poem does not descend into outright anger or despair. Instead, Sandburg captures a quiet dignity in the shovelman’s routine. He eats his meal without complaint, returns to work, and performs his task with precision. There is a stoic acceptance in his actions, a resilience that Sandburg often celebrated in his working-class subjects.

Yet, there is also an undercurrent of resignation. The shovelman does not protest or even seem to notice the disparity between his life and that of the passengers. His acceptance may reflect the numbing effect of relentless labor, or perhaps a pragmatic understanding that his position in society is immutable. This emotional complexity makes the poem all the more poignant—it is not a call to revolution, but a sober acknowledgment of an entrenched system.

Comparative and Philosophical Readings

Sandburg’s poem can be fruitfully compared to other works of early 20th-century labor poetry, such as Edwin Markham’s "The Man with the Hoe" (1899), which similarly depicts the exhaustion of the working class. Both poems draw on realist and socialist traditions, portraying laborers with empathy while critiquing the systems that exploit them.

Philosophically, the poem resonates with Marxist critiques of capitalism, particularly the idea that workers are alienated from the products of their labor. The shovelman’s efforts directly enable the comfort of the dining car passengers, yet he derives no benefit from their luxury. This dynamic mirrors Marx’s argument that under capitalism, labor is reduced to a commodity, and workers are estranged from the value they create.

At the same time, Sandburg’s humanist perspective prevents the poem from becoming purely ideological. His focus on the shovelman’s quiet endurance lends the poem a universal quality—it is not just about class struggle, but about the broader human condition of perseverance in the face of hardship.

Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of "Child of the Romans"

More than a century after its publication, "Child of the Romans" remains strikingly relevant. In an era of growing economic inequality, gig labor, and debates over workers’ rights, Sandburg’s depiction of the invisible laborer resonates deeply. The poem challenges readers to recognize the often-unseen toil that underpins modern comfort, urging a more equitable and humane society.

Ultimately, Sandburg’s genius lies in his ability to compress vast social commentary into a few precise lines. Through stark contrasts, vivid imagery, and quiet emotional depth, "Child of the Romans" compels us to see the worker not as a faceless drudge, but as a dignified individual—one whose labor, though overlooked, is essential to the machinery of the world. In doing so, Sandburg affirms poetry’s power to bear witness to injustice while honoring the resilience of the human spirit.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.