The Stream of Life

Arthur Hugh Clough

1819 to 1861

O stream descending to the sea,

Thy mossy banks between,

The flow’rets blow, the grasses grow,

The leafy trees are green.

In garden plots the children play,

The fields the labourers till,

And houses stand on either hand,

And thou descendest still.

O life descending into death,

Our waking eyes behold,

Parent and friend thy lapse attend,

Companions young and old.

Strong purposes our mind possess,

Our hearts affections fill,

We toil and earn, we seek and learn,

And thou descendest still.

O end to which our currents tend,

Inevitable sea,

To which we flow, what do we know,

What shall we guess of thee?

A roar we hear upon thy shore,

As we our course fulfil;

Scarce we divine a sun will shine

And be above us still.

Arthur Hugh Clough's The Stream of Life

Arthur Hugh Clough’s The Stream of Life is a profound meditation on existence, mortality, and the inexorable passage of time. Through its deceptively simple structure and lyrical flow, the poem engages with deep philosophical questions about human purpose, the nature of life’s journey, and the mysteries that lie beyond death. Written in the mid-19th century, a period marked by rapid industrialization, scientific advancement, and religious doubt, Clough’s work reflects the anxieties and introspections of the Victorian era. This essay will explore the poem’s thematic concerns, its use of natural imagery as metaphor, its emotional resonance, and its place within the broader context of 19th-century literature.

The Poem as a Meditation on Time and Mortality

At its core, The Stream of Life is an extended metaphor comparing human existence to a river flowing inevitably toward the sea—a traditional symbol of eternity or death. The poem opens with an apostrophe to the stream, immediately establishing its central conceit:

O stream descending to the sea,

Thy mossy banks between,

The flow’rets blow, the grasses grow,

The leafy trees are green.

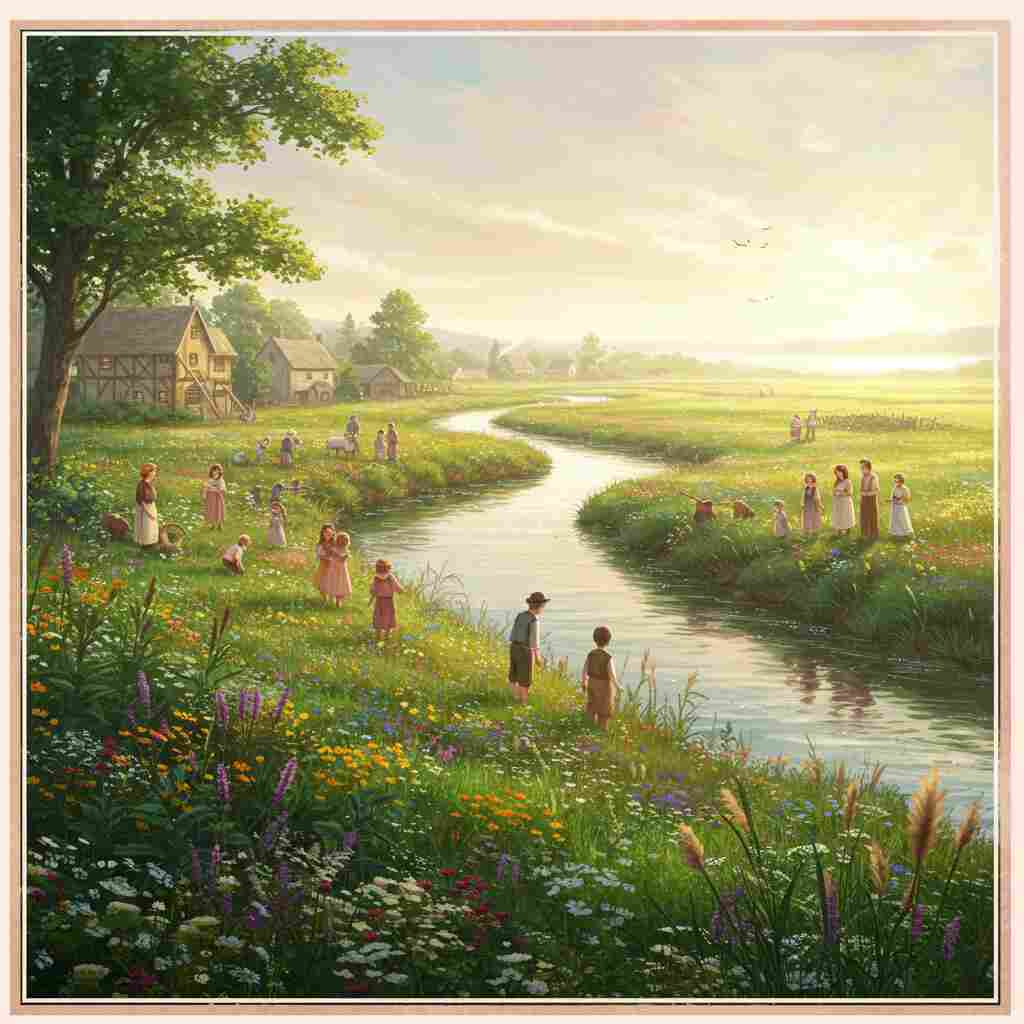

The imagery here is pastoral and serene, evoking a natural world that thrives even as the stream moves ceaselessly forward. This juxtaposition of movement and stasis—the flowing water against the static banks—introduces one of the poem’s key tensions: the contrast between human endeavors, which seem permanent and meaningful in the moment, and the relentless progression of time, which renders all things transient.

Clough extends this metaphor in the second stanza, introducing human activity:

In garden plots the children play,

The fields the labourers till,

And houses stand on either hand,

And thou descendest still.

Here, the poem shifts from pure natural description to a vision of human life unfolding alongside the stream. The children at play, the laborers tilling the soil, and the houses standing firm all suggest stability and continuity. Yet the refrain—And thou descendest still—serves as a sobering reminder that despite these signs of life and industry, the stream (and by extension, time itself) never pauses. The effect is both beautiful and melancholic, capturing the bittersweet awareness that life’s most vibrant moments are fleeting.

The Inevitability of Death and the Limits of Human Knowledge

The third stanza makes the poem’s existential concerns explicit by shifting from the stream to life itself:

O life descending into death,

Our waking eyes behold,

Parent and friend thy lapse attend,

Companions young and old.

The phrase life descending into death removes any ambiguity about the poem’s central metaphor: the stream is life, and the sea is death. The mention of parent and friend underscores the universality of this journey—death comes for all, regardless of age or relationship. The tone here is not one of despair but of quiet acceptance, a recognition that mortality is an inescapable part of existence.

Clough then turns to human striving in the fourth stanza:

Strong purposes our mind possess,

Our hearts affections fill,

We toil and earn, we seek and learn,

And thou descendest still.

These lines emphasize the paradox of human life: we are driven by ambitions, love, labor, and curiosity, yet all these efforts unfold within the unstoppable current of time. The repetition of descendest still at the end of each stanza reinforces the inevitability of decline, creating a rhythmic inevitability that mirrors the poem’s thematic preoccupation with fate.

The final stanza confronts the ultimate uncertainty of what lies beyond death:

O end to which our currents tend,

Inevitable sea,

To which we flow, what do we know,

What shall we guess of thee?

The sea, representing death, is described as inevitable, yet also profoundly mysterious. The questions Clough poses—what do we know, what shall we guess of thee?—reflect the Victorian crisis of faith, where traditional religious assurances were being eroded by scientific and philosophical skepticism. The poem does not offer answers but instead lingers on the uncertainty, a stance characteristic of much Victorian literature, which often grappled with the tension between faith and doubt.

The closing lines introduce a final, haunting image:

A roar we hear upon thy shore,

As we our course fulfil;

Scarce we divine a sun will shine

And be above us still.

The roar of the sea suggests both the terror and majesty of death, while the mention of a sun that will shine / And be above us still offers a faint glimmer of transcendence. Whether this sun symbolizes divine presence, the continuation of nature, or mere indifferent cosmic order is left ambiguous—an ambiguity that deepens the poem’s philosophical weight.

Literary and Historical Context

Clough wrote during a period of profound intellectual upheaval. The mid-19th century saw the rise of Darwinism, geological discoveries that challenged biblical timelines, and growing secularization. Poets like Clough, Matthew Arnold, and Alfred Tennyson often explored themes of doubt, existential searching, and the struggle to find meaning in a rapidly changing world.

The Stream of Life shares thematic ground with Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which also meditates on mortality and the possibility of an afterlife, as well as Arnold’s Dover Beach, with its lament for the Sea of Faith retreating. Unlike Tennyson, who tentatively reaches for hope, or Arnold, who mourns faith’s decline, Clough’s tone is more restrained, accepting uncertainty without either despair or consolation.

Biographically, Clough’s own religious struggles inform the poem. Educated at Oxford during the Tractarian movement (which sought to revive High Church Anglicanism), he later experienced severe doubt and resigned his fellowship, unable to reconcile his faith with his intellectual honesty. This personal tension between belief and skepticism permeates The Stream of Life, making it not just a general meditation on mortality but also a deeply personal reflection on the human condition.

Literary Devices and Emotional Impact

Clough’s use of refrain (And thou descendest still) creates a hypnotic, almost fatalistic rhythm, reinforcing the poem’s central theme of inexorable progression. The natural imagery—flowers, grasses, trees, the sea—grounds the abstract meditation in tangible, sensory details, making the poem’s philosophical musings feel immediate and visceral.

The emotional impact of the poem lies in its quiet solemnity. Unlike more dramatic Victorian poems that rail against death or seek grand consolations, The Stream of Life adopts a tone of measured acceptance. There is sorrow in its recognition of life’s brevity, but also a kind of peace in its acknowledgment of nature’s continuity. The final image of the sun, shining indifferently above, suggests that while individual lives end, the world endures—a thought that is neither comforting nor despairing, but simply true.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Clough’s Vision

The Stream of Life remains a poignant and thought-provoking work because it captures a universal human experience—the awareness of our own mortality—with both clarity and lyrical beauty. Its strength lies in its restraint; it does not seek to resolve the mysteries it raises but instead invites the reader to sit with them. In doing so, it embodies the Victorian era’s intellectual honesty and emotional depth, offering no easy answers but a profound engagement with life’s most enduring questions.

Clough’s poem, like the stream it describes, moves steadily toward its conclusion, leaving behind not a definitive statement, but an echo—a whisper of the eternal in the transient, the unknown in the known. It is this delicate balance between acceptance and inquiry that makes The Stream of Life a lasting contribution to the canon of English poetry, one that continues to resonate with readers confronting the same timeless uncertainties today.

Version 3

The idea of transforming The Stream of Life into a call-and-response style rap came from the poem’s own internal rhythm and its dialogue with time. Arthur Hugh Clough’s verses trace life’s gentle, inevitable flow toward death, but they also echo with unspoken questions and unanswered thoughts. That tension between motion and meaning—between what is seen and what is guessed—felt perfect for a dual-voiced arrangement. By using a call-and-response format, I wanted to give voice to that silent counterpart: the soul’s response to life, the whisper of mortality, or even the future self reflecting on the past.

In performance, this structure allows the poem to become more than just a solitary meditation; it becomes a conversation across time, between youth and age, life and death, hope and resignation. Rap—particularly in its more introspective or conscious forms—is uniquely suited to this kind of poetic reflection. Its rhythm supports clarity, while its cultural roots in dialogue, resistance, and identity give the piece emotional urgency. The call lines stay faithful to Clough’s original text, while the responses expand upon them, introducing modern emotional tones: doubt, weariness, nostalgia, and fleeting glimpses of transcendence. It’s a bold, contemporary reinterpretation that aims to draw modern ears into the timeless current of the poem.

🎤 Call and Response Lyrical Adaptation: The Stream of Life

O stream descending to the sea,

(You carry time away from me)

Thy mossy banks between,

(Soft earth that cradles all we've been)

The flow’rets blow, the grasses grow,

(Then fade beneath the current’s flow)

The leafy trees are green.

(But green turns brown, and brown unseen)

In garden plots the children play,

(Their laughter echoes into grey)

The fields the labourers till,

(Their sweat feeds roots that time will still)

And houses stand on either hand,

(Like watchers mute on borrowed land)

And thou descendest still.

(You never pause, you never will)

O life descending into death,

(Each breath we take is one breath less)

Our waking eyes behold,

(Yet sleep is always creeping cold)

Parent and friend thy lapse attend,

(All hands must part, all journeys bend)

Companions young and old.

(They fade like fire when night takes hold)

Strong purposes our mind possess,

(But what survives the weariness?)

Our hearts affections fill,

(Yet every love must one day still)

We toil and earn, we seek and learn,

(But none can buy what none return)

And thou descendest still.

(Time flows indifferent to our will)

O end to which our currents tend,

(You call us all, we can’t pretend)

Inevitable sea,

(The final hush, the mystery)

To which we flow, what do we know,

(A shimmer lost in undertow)

What shall we guess of thee?

(A light, a void, or just... to be?)

A roar we hear upon thy shore,

(It shakes the soul, we ask for more)

As we our course fulfil;

(But never know the plan until)

Scarce we divine a sun will shine

(Beyond the dark, beyond decline)

And be above us still.

(Perhaps it waits—perhaps it will.)

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.