Gray Eyes

Nora Hopper Chesson

1871 to 1906

Gray eyes and gold hair,

Who remembers you were fair,

When on middle earth you were

Gray Eyes?

You were half a fairy then:

Are you claimed of them again,

Now you've gone beyond my ken,

Gray Eyes?

Sailing over perilous seas,

Dreaming under rowan-trees;

Quiet heart and quiet hand,

Are you back in Fairyland,

Gray Eyes?

You were cold as winter snow

To the soul that sought to know,

Creed and whimsy old and new,

Heights and deeps and dreams of you,

Gray Eyes?

Are you kinder now my feet

Lose your track in lane and street,

For all time, O cold and sweet

Gray Eyes?

Do you wish that you could set

Me the lesson to forget

That our souls had ever met,

Gray Eyes?

Much I sowed and naught I reap,

Come and give me dreams to keep —

Be not as of old you were,

Cold as death, as void of care,

Gray Eyes?

Nay, but come without the change,

I should find the warm heart strange.

Come to me, as cold as snow —

For I loved you thus, you know,

Gray Eyes.

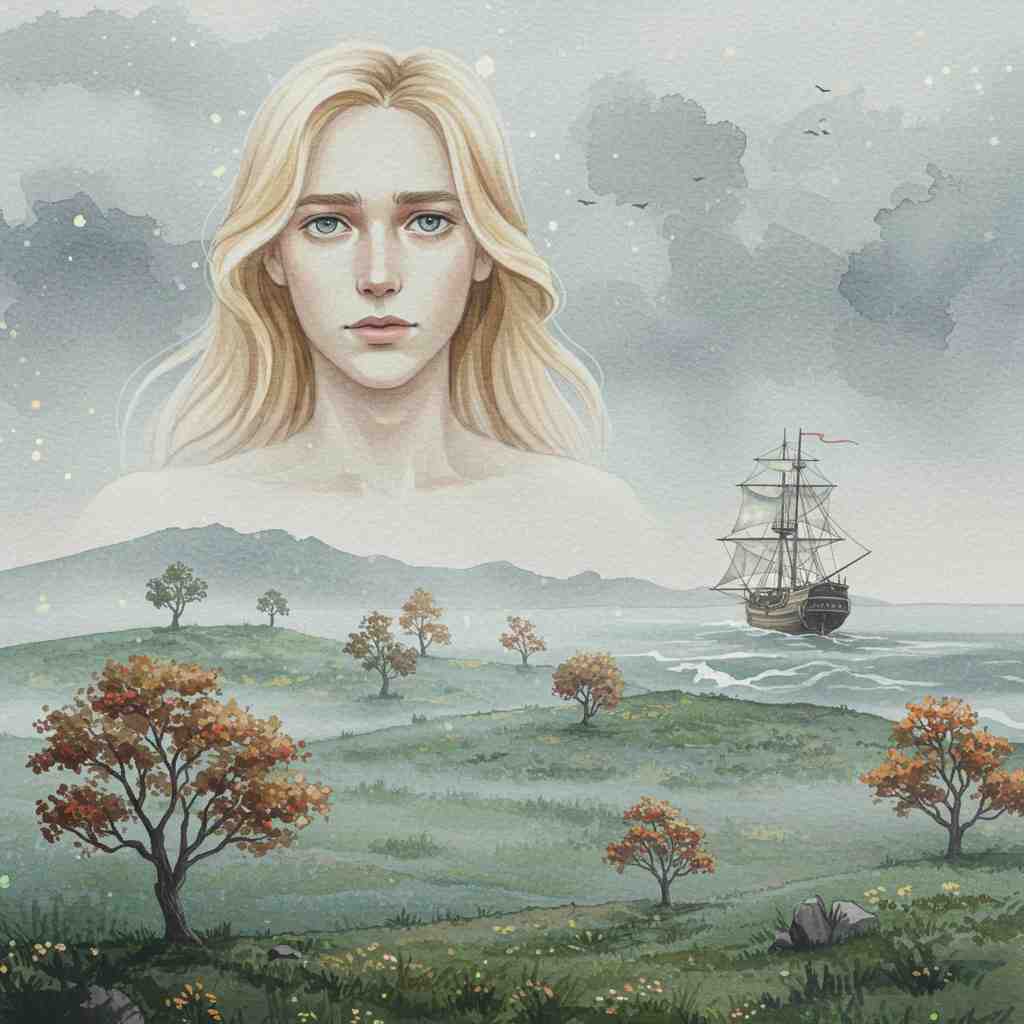

Nora Hopper Chesson's Gray Eyes

Nora Hopper Chesson's poem "Gray Eyes" presents a haunting meditation on loss, memory, and the ephemeral nature of human connection. Published during the late Victorian era, this lyrical composition embodies the period's fascination with folklore and fairy mythology while simultaneously exploring deeply personal themes of unrequited love and emotional distance. Through its evocative imagery, musical cadence, and interrogative structure, the poem creates a liminal space where the mundane and the otherworldly intersect, inviting readers to contemplate the mysterious boundaries between presence and absence, memory and forgetting, mortal life and ethereal existence.

This analysis aims to unravel the complex tapestry of "Gray Eyes," examining its formal qualities, thematic preoccupations, and cultural resonances. By situating the poem within its historical context and exploring its intricate engagement with Irish folklore and Victorian poetic conventions, we can appreciate how Chesson crafts a work that transcends simple categorization. Her poem operates simultaneously as elegy, love lyric, and folkloric meditation, demonstrating the versatility and emotional depth that characterized the Celtic Revival movement's literary contributions.

Historical Context and the Celtic Revival

Nora Hopper Chesson (1871-1906) wrote during a period of significant cultural and literary transformation in Ireland and Britain. As a poet associated with the Celtic Revival (also known as the Irish Literary Renaissance), Chesson participated in a broader cultural movement that sought to reclaim and reimagine Celtic mythology, folklore, and literary traditions. The movement emerged partly as a response to English cultural dominance and partly as an attempt to forge a distinctive Irish literary identity that drew upon the nation's rich mythological heritage.

The late 19th century witnessed a renewed interest in fairy lore across the British Isles, influenced by anthropological studies, folklore collections, and a general Victorian fascination with the supernatural. This cultural climate provided fertile ground for Chesson's poetic explorations of fairy motifs and liminal experiences. The poem's repeated references to "Fairyland" and its characterization of the beloved as "half a fairy" position "Gray Eyes" within this tradition of fairy poetry, which includes works by contemporaries such as W.B. Yeats, whose collection "The Celtic Twilight" (1893) similarly explored the intersection between the mortal and fairy worlds.

Chesson's Irish heritage informed her literary sensibilities, though she spent much of her life in England. This biographical detail mirrors the cultural hybridity evident in "Gray Eyes," which blends Irish folkloric elements with more conventional Victorian poetic forms. The poem thus exemplifies the cross-cultural pollination that characterized much Revival literature, creating a distinctive voice that navigates between traditions.

Formal Analysis

Structure and Rhythm

"Gray Eyes" consists of seven stanzas of varying lengths, creating a fluid, almost musical structure that resists rigid formalization. This structural flexibility reflects the poem's thematic preoccupation with boundaries and transitions. The shorter stanzas (particularly the third and final stanzas) create momentary pauses in the poem's progression, suggesting emotional intensity that cannot be sustained for extended periods.

The poem's rhythm alternates between trimeter and dimeter lines, creating a lilting cadence reminiscent of folk ballads. This musicality is particularly evident in lines such as "Sailing over perilous seas, / Dreaming under rowan-trees," where the trochaic meter creates a gentle rocking motion that evokes both seafaring and dreaming. The poem's rhythmic structure thus reinforces its thematic concern with journeys between worlds.

Sound Patterns

Chesson employs subtle internal rhymes and consonance throughout the poem, creating auditory echoes that enhance its incantatory quality. The repetition of "Gray Eyes" at crucial moments functions as both refrain and invocation, suggesting the speaker's persistent attempt to summon or address the absent beloved. The poem's sound patterns create a hypnotic effect, drawing readers into a dreamlike state that mirrors the liminal consciousness the poem describes.

The careful modulation of vowel sounds contributes significantly to the poem's emotional register. The shift from the open vowels in "fair" and "then" to the more constricted sounds in "cold" and "snow" traces an emotional trajectory from openness to constraint, reflecting the speaker's experience of the beloved's emotional unavailability.

Thematic Explorations

Liminality and Boundaries

Central to "Gray Eyes" is the concept of liminality—the state of being between worlds or states of existence. The poem positions its subject in an indeterminate space between mortality and fairy enchantment: "You were half a fairy then: / Are you claimed of them again, / Now you've gone beyond my ken." This ambiguous positioning creates tension between presence and absence, knowledge and uncertainty.

The motif of crossing boundaries appears repeatedly: "Sailing over perilous seas" suggests a journey to the otherworld, while "gone beyond my ken" establishes the unbridgeable distance between speaker and subject. In Celtic mythology, bodies of water often represent thresholds between the mortal world and the fairy realm, making the seafaring imagery particularly significant. The poem thus engages with traditional folkloric conceptions of fairy abduction or migration, where mortals cross into the fairy world, often never to return.

Emotional Distance and Unrequited Desire

Beneath its folkloric framework, "Gray Eyes" presents a poignant meditation on emotional unavailability and unrequited love. The repeated characterization of the beloved as "cold as winter snow" establishes their emotional remoteness, while the speaker's persistent questioning reveals their unfulfilled desire for connection. This emotional dynamic creates the poem's central paradox: the speaker simultaneously laments and cherishes the beloved's coldness, eventually acknowledging, "For I loved you thus, you know."

This complex emotional stance reflects the Victorian literary tradition of idealizing unattainable love. By framing the beloved's emotional distance through fairy mythology, Chesson transforms what might otherwise be a conventional lyric of unrequited love into something more ambiguous and mysterious. The fairy motif serves as a metaphorical framework for understanding emotional inaccessibility; just as fairies exist alongside but separate from the mortal world, the beloved exists in proximity to but emotionally distant from the speaker.

Memory and Forgetting

Throughout the poem, memory functions as both comfort and torment for the speaker. The opening question, "Who remembers you were fair," establishes memory as a central concern, suggesting that remembrance itself might be a form of possession when physical presence is impossible. Later, the speaker wonders if the beloved wishes to "set / Me the lesson to forget / That our souls had ever met," positioning forgetting as a potential but undesired release from emotional attachment.

This preoccupation with memory reflects broader Victorian anxieties about the reliability and durability of human connections in a rapidly changing world. By framing memory as something that must be actively maintained—"Come and give me dreams to keep"—the poem suggests that remembrance requires ongoing effort, particularly when its object exists in an indeterminate state between presence and absence.

Imagery and Symbolism

The Gray Eyes

The titular "gray eyes" function as the poem's central symbol, representing ambiguity, liminality, and emotional inscrutability. Gray occupies an intermediate position between black and white, making it an appropriate color to symbolize the beloved's liminal status between fairy and human realms. The eyes themselves represent windows to the soul that paradoxically reveal little, reflecting the poem's preoccupation with knowing and not knowing.

The persistent invocation of "Gray Eyes" throughout the poem transforms the phrase from simple physical description to symbolic identifier. By the poem's conclusion, "Gray Eyes" has become a complex signifier that encompasses all the beloved's contradictory qualities: coldness and sweetness, presence and absence, mortality and fairy nature.

Fairy Symbols

Chesson incorporates several traditional fairy symbols that would have been recognizable to her contemporary readers. The "rowan-trees" mentioned in the third stanza carry particular significance in Celtic folklore, where rowan (mountain ash) was believed to offer protection against fairy enchantment. The juxtaposition of "Dreaming under rowan-trees" creates an intriguing tension, suggesting both vulnerability to and protection from fairy influence.

The reference to "Fairyland" explicitly connects the poem to the folk tradition of fairy abduction narratives, where mortals are lured or taken to the fairy realm. In many of these narratives, time passes differently in Fairyland, and those who return find they have been away for years or centuries. This temporal disjunction adds another dimension to the poem's exploration of separation and loss.

The Interrogative Mode

One of the poem's most distinctive features is its reliance on questions rather than declarations. Six of the seven stanzas pose direct questions to the absent beloved, creating a one-sided dialogue that emphasizes the speaker's uncertainty and the beloved's silence. This interrogative mode serves multiple purposes: it establishes the beloved's inaccessibility, creates a sense of ongoing conversation despite physical separation, and involves readers in the process of wondering and seeking.

The final stanza provides the poem's only definitive statement, shifting from question to declaration: "Nay, but come without the change, / I should find the warm heart strange." This transition marks an emotional resolution of sorts, as the speaker accepts and even embraces the beloved's coldness. The concluding assertion, "For I loved you thus, you know," suggests that desire persists not despite but because of the beloved's remote, fairy-like nature.

Comparative Contexts

Yeats and the Fairy Tradition

Chesson's treatment of fairy themes invites comparison with W.B. Yeats, whose poetry similarly explores the intersection of mortal and fairy worlds. Both poets draw upon Irish folklore while adapting it to express personal and universal emotional experiences. However, while Yeats often presents the fairy realm as seductive but dangerous to mortals (as in "The Stolen Child"), Chesson's poem complicates this dynamic by suggesting that the beloved was already "half a fairy" before their departure, implying an inherent otherworldliness rather than an abduction narrative.

Christina Rossetti and Unrequited Love

The poem's treatment of emotional distance shares thematic concerns with Christina Rossetti's love poetry, particularly works like "Echo" and "Remember," which similarly explore absence and memory. Like Rossetti, Chesson transforms the conventional Victorian love lyric by emphasizing separation rather than union and by finding value in unfulfilled desire. The conclusion of "Gray Eyes," with its paradoxical embrace of the beloved's coldness, echoes Rossetti's complex approach to desire and renunciation.

Philosophical Dimensions

The Ethics of Memory

The poem raises subtle ethical questions about remembrance and obligation. The speaker's persistent questioning suggests a refusal to release the beloved from memory, even as they wonder if forgetting might be the beloved's preference: "Do you wish that you could set / Me the lesson to forget / That our souls had ever met." This tension between holding on and letting go raises broader philosophical questions about the ethics of remembrance and the potential burden that being remembered might place on the remembered.

Desire and Paradox

"Gray Eyes" engages with philosophical paradoxes surrounding desire, particularly the concept that we often desire precisely what remains unavailable to us. The speaker's final acceptance—even embrace—of the beloved's coldness suggests a sophisticated understanding of desire's contradictory nature. By acknowledging, "For I loved you thus, you know," the speaker recognizes that the beloved's very remoteness constitutes their appeal, challenging conventional romantic narratives that prioritize reciprocity and fulfillment.

Cultural Significance and Legacy

Chesson's poem exemplifies the Celtic Revival's distinctive contribution to Victorian poetry, blending folkloric elements with personal emotional exploration. While not as widely recognized as works by Yeats or Lady Gregory, "Gray Eyes" represents an important female voice in a movement often dominated by male perspectives. The poem's subtle incorporation of fairy mythology demonstrates how Revival writers transformed traditional materials to address contemporary emotional and philosophical concerns.

From a contemporary perspective, the poem's exploration of ambiguous boundaries between states of being resonates with postmodern preoccupations with liminality and fluid identities. Its treatment of memory and loss speaks to universal human experiences while remaining grounded in its specific cultural context. The poem thus demonstrates how literary works can transcend their historical moment by addressing enduring emotional and existential questions through culturally specific symbolism and imagery.

Conclusion

Nora Hopper Chesson's "Gray Eyes" achieves remarkable emotional and philosophical complexity within its seemingly simple structure. By weaving together Celtic fairy lore with a deeply personal meditation on unrequited love, the poem creates a multifaceted exploration of absence, memory, and desire. Its persistent questioning creates space for readers to insert themselves into the poem's emotional landscape, contemplating their own experiences of loss and longing.

The poem's enduring appeal lies partly in its ambiguity—we never learn precisely who or what "Gray Eyes" is, whether a mortal lover who has died, a fairy being who has returned to their own realm, or some combination of both. This indeterminacy allows the poem to function simultaneously as elegy, love lyric, and folkloric meditation, demonstrating the versatility of fairy symbolism as a framework for exploring human emotional experience.

In its delicate balance between specificity and universality, "Gray Eyes" exemplifies how poetry can transform personal emotion into art that resonates across time and cultural boundaries. Chesson's work deserves recognition not only for its contribution to the Celtic Revival but also for its sophisticated exploration of emotional dynamics that continue to characterize human relationships. Through its haunting imagery and musical language, "Gray Eyes" invites readers to contemplate the mysterious boundaries between presence and absence, memory and forgetting, and to recognize the paradoxical nature of desire itself.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.