On an Infant's Grave

John Clare

1793 to 1864

Beneath the sod where smiling creep

The daisies into view,

The ashes of an Infant sleep,

Whose soul’s as smiling too;

Ah! doubly happy, doubly blest,

(Had I so happy been!)

Recall’d to heaven’s eternal rest,

Ere it knew how to sin.

Thrice happy Infant! great the bliss

Alone reserv’d for thee;

Such joy ’twas my sad fate to miss,

And thy good luck to see;

For oh! when all must rise again,

And sentence then shall have,

What crowds will wish with me, in vain,

They’d fill’d an infant’s grave.

John Clare's On an Infant's Grave

John Clare’s "On an Infant’s Grave" is a poignant meditation on mortality, innocence, and the paradoxical blessings of early death. Written in the early 19th century, the poem reflects Clare’s personal struggles with grief, poverty, and mental illness, while also engaging with broader Romantic-era preoccupations with nature, childhood, and the afterlife. Through its deceptively simple language and lyrical economy, the poem raises profound theological and existential questions, offering both consolation and unsettling ambiguity. This analysis will explore the poem’s thematic concerns, its emotional resonance, its historical and biographical context, and its place within the tradition of elegiac poetry.

Themes of Innocence, Mortality, and Divine Mercy

At its core, "On an Infant’s Grave" grapples with the Christian conception of original sin and the idea that an infant, having died before moral accountability, is granted immediate salvation. The speaker envies the buried child, not only for its escape from earthly suffering but for its guaranteed entry into "heaven’s eternal rest" (line 7). The infant is "doubly happy, doubly blest" (line 5) because it has avoided the moral failings that plague human existence. This sentiment echoes the theological doctrine of mors immatura—the notion that those who die young are spared the corruption of adulthood.

Clare’s treatment of this theme is both tender and unsettling. While the poem ostensibly offers comfort—the child’s soul is "as smiling too" (line 4) as the daisies above its grave—there is an undercurrent of despair in the speaker’s voice. The exclamation "Had I so happy been!" (line 6) suggests a profound weariness with life, a sentiment Clare himself struggled with throughout his years of hardship. The poem thus functions as both an elegy for the dead and a lament for the living, who must endure the burdens of sin and judgment.

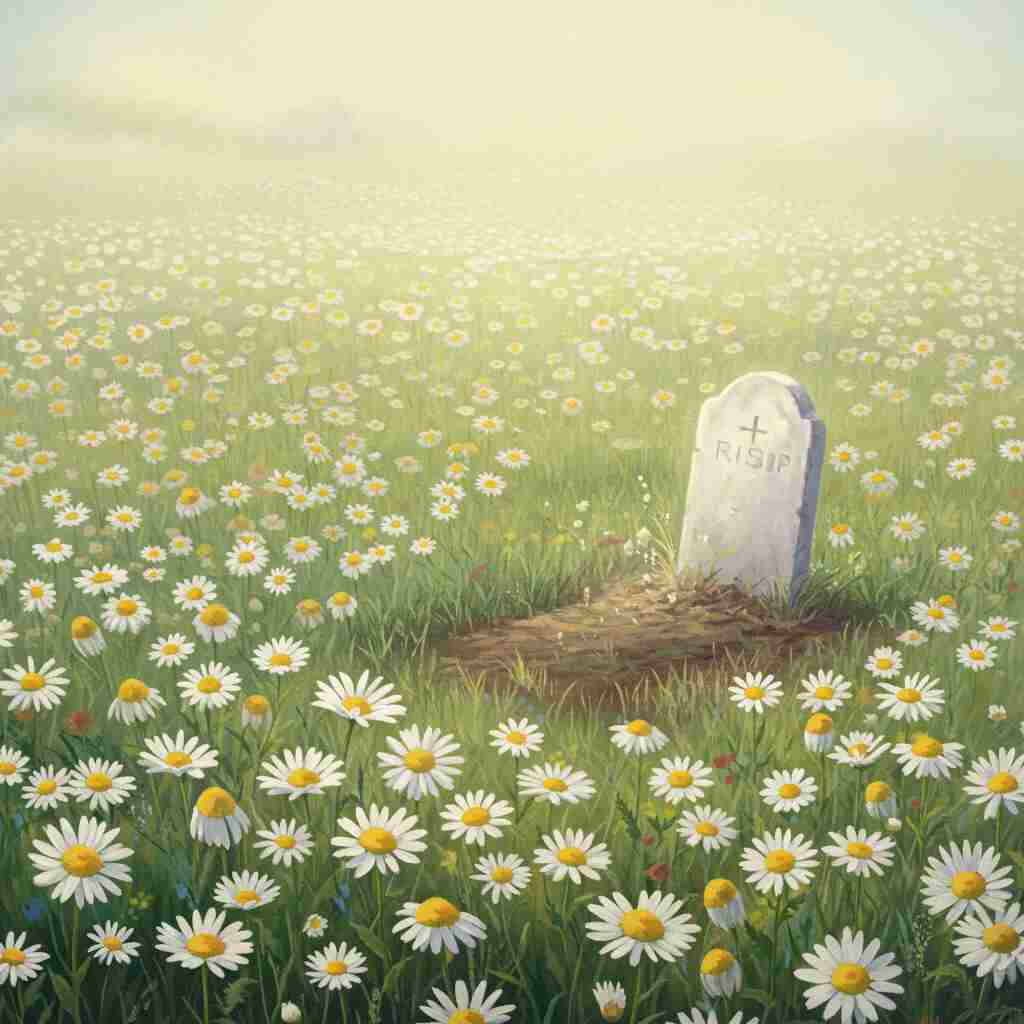

Nature and the Sublime

Like many Romantic poets, Clare finds solace and symbolism in the natural world. The opening lines—

"Beneath the sod where smiling creep

The daisies into view,"

—evoke a serene, almost pastoral image of death. The daisies, symbols of innocence and renewal, "smile" as they grow over the grave, suggesting nature’s indifference to human sorrow. Yet this indifference is not cruel; rather, it offers a quiet kind of beauty, a reminder of cyclical regeneration. The infant’s grave is not a site of horror but of gentle absorption into the earth, reinforcing the Romantic ideal of death as a return to nature.

However, Clare’s treatment of nature is more complex than mere sentimentalism. Unlike Wordsworth, who often depicts nature as a moral guide, Clare’s landscapes are tinged with melancholy. The daisies may smile, but the speaker does not share their ease. The contrast between the infant’s peaceful rest and the speaker’s anguished existence creates a tension between the natural world’s serenity and human suffering.

Theological and Philosophical Underpinnings

The poem engages with theodicy—the question of why a benevolent God permits suffering. The speaker’s assertion that the infant is "thrice happy" (line 9) because it escaped life’s trials suggests a deeply pessimistic view of human existence. The final stanza takes this further, imagining the Day of Judgment when "all must rise again" (line 13). The speaker predicts that many will envy the infant, wishing they too had died before moral accountability. This is a startling inversion of traditional Christian consolation, which typically emphasizes resurrection and redemption. Instead, Clare’s speaker implies that salvation is most certain for those who never lived long enough to fall from grace.

This perspective aligns with Clare’s own fraught relationship with religion. Though he was raised Anglican, his later writings reveal a man tormented by doubt and despair. The poem’s ambivalence—its simultaneous longing for divine mercy and implicit critique of a world where death is preferable to life—reflects Clare’s personal struggles. Unlike the more orthodox faith of poets like George Herbert or Christina Rossetti, Clare’s spirituality is shadowed by existential dread.

Biographical Context: Clare’s Personal Grief

John Clare’s life was marked by profound loss, including the deaths of several of his own children. His first son, John, died in infancy, and Clare’s journals reveal his deep sorrow over these losses. "On an Infant’s Grave" may thus be read as an expression of personal grief, not just a philosophical meditation. The poem’s intimacy—its direct address to the child ("Ah! doubly happy, doubly blest")—suggests a mourner’s voice rather than an abstract theological argument.

Moreover, Clare’s own mental health struggles (he spent the latter part of his life in an asylum) lend the poem an added layer of pathos. The speaker’s longing for the peace of the grave resonates with Clare’s documented bouts of depression. The poem’s closing lines—

"What crowds will wish with me, in vain,

They’d fill’d an infant’s grave."

—could be read as an expression of suicidal ideation, a desperate wish for escape. This interpretation aligns with Clare’s later poetry, which often blurs the line between elegy and personal lament.

Comparative Readings: Clare and the Elegiac Tradition

Clare’s poem can be usefully compared to other Romantic-era elegies, such as Wordsworth’s "We Are Seven" or Blake’s "The Chimney Sweeper." Like Wordsworth, Clare explores the innocence of childhood, but whereas Wordsworth’s young girl insists on the continued presence of her dead siblings, Clare’s speaker is haunted by absence. Blake’s "The Chimney Sweeper" similarly contrasts the purity of dead children with the corruption of the living, but Blake’s tone is more satirical, critiquing social injustice, whereas Clare’s grief is more personal and introspective.

Another illuminating comparison is with Emily Dickinson’s "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers," which also portrays the dead as blissfully removed from life’s turmoil. Both poets employ nature imagery to underscore the divide between the living and the dead, but Dickinson’s tone is more detached, even ironic, while Clare’s is suffused with raw emotion.

Conclusion: The Poem’s Enduring Power

"On an Infant’s Grave" endures because it speaks to universal fears and longings—the fear of moral failure, the longing for peace, the ache of parental grief. Clare’s ability to condense profound existential questions into a brief lyric is a testament to his poetic skill. The poem’s simplicity belies its depth; its quiet cadences linger in the mind, inviting both comfort and unease.

Ultimately, the poem does not offer easy answers. It is a work of contradictions—celebrating the infant’s salvation while mourning the necessity of such salvation, finding beauty in nature while acknowledging its indifference. In this tension, Clare captures the essence of human sorrow and the fragile hope for something beyond it. The infant’s grave is both a site of loss and a symbol of transcendence, a duality that makes the poem as moving today as it was nearly two centuries ago.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.