O, that this too too solid flesh would melt

William Shakespeare

1564 to 1616

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew!

Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d

His canon ’gainst self-slaughter! O God! God!

How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Fie on’t! ah fie! ’tis an unweeded garden,

That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely. That it should come to this!

But two months dead: nay, not so much, not two:

So excellent a king; that was, to this,

Hyperion to a satyr; so loving to my mother

That he might not beteem the winds of heaven

Visit her face too roughly. Heaven and earth!

Must I remember? why, she would hang on him,

As if increase of appetite had grown

By what it fed on: and yet, within a month—

Let me not think on’t—Frailty, thy name is woman!—

A little month; or ere those shoes were old

With which she follow’d my poor father’s body,

Like Niobe, all tears:—why she, even she—

O, God! a beast, that wants discourse of reason,

Would have mourn’d longer—married with my uncle,

My father’s brother, but no more like my father

Than I to Hercules: within a month:

Ere yet the salt of most unrighteous tears

Had left the flushing in her galled eyes,

She married. O, most wicked speed, to post

With such dexterity to incestuous sheets!

It is not nor it cannot come to good:

But break, my heart; for I must hold my tongue.

William Shakespeare's O, that this too too solid flesh would melt

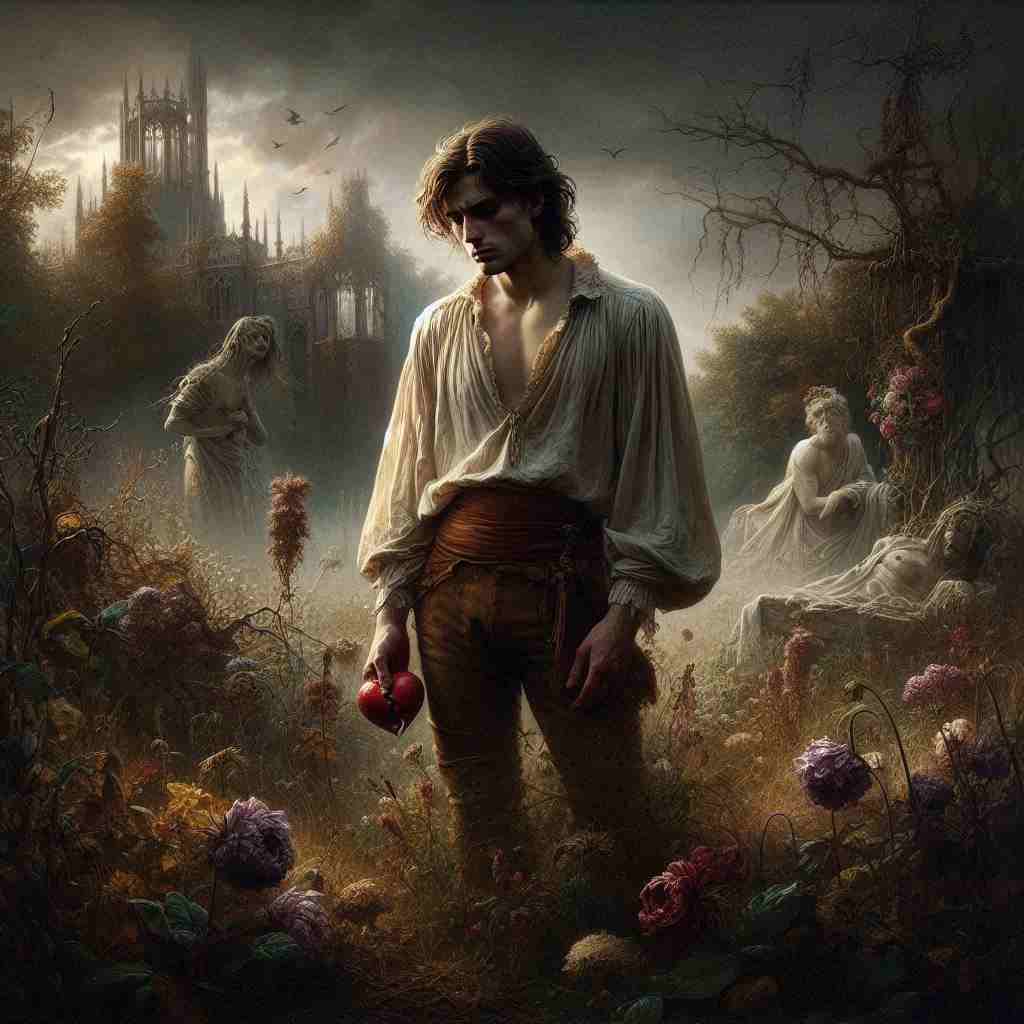

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a masterpiece of psychological depth, philosophical inquiry, and linguistic brilliance. Among its many soliloquies, Hamlet’s anguished lament in Act 1, Scene 2—"O, that this too too solid flesh would melt"—stands as one of the most revealing and emotionally charged moments in the play. This soliloquy not only establishes Hamlet’s profound despair but also introduces key themes of mortality, corruption, and existential disillusionment. Through a close reading of this passage, we can explore Shakespeare’s use of language, the historical and religious context of suicide, the psychological realism of grief, and the broader philosophical questions that define Hamlet as a tragedy of the human condition.

The Weight of Flesh: Mortality and the Desire for Dissolution

The soliloquy opens with a visceral longing for self-annihilation:

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew!

Hamlet’s wish for his body to dissolve into nothingness is both poetic and deeply existential. The repetition of "too too solid" emphasizes the unbearable physicality of his existence—his flesh is not just solid but excessively so, a prison from which he yearns to escape. The imagery of melting and thawing suggests a return to a more elemental, incorporeal state, evoking both relief and oblivion. This opening line also carries biblical undertones; the idea of flesh returning to dust echoes Genesis 3:19 ("for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return"), reinforcing the theme of mortality.

However, Hamlet’s desire for dissolution is immediately complicated by religious doctrine:

Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d

His canon ’gainst self-slaughter!

Here, Shakespeare situates Hamlet’s despair within the theological constraints of the Elizabethan era. Suicide was considered a mortal sin in Christian doctrine, condemned as an act of defiance against God’s will. The term "canon" refers to divine law, and Hamlet’s frustration underscores his entrapment—he cannot escape his suffering even through death. This tension between personal anguish and religious prohibition adds a layer of tragic irony to Hamlet’s predicament: he is tormented by life but forbidden from ending it.

The World as an "Unweeded Garden": Corruption and Decay

Hamlet’s despair extends beyond his personal suffering to a broader condemnation of the world:

How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

The accumulation of adjectives—"weary, stale, flat and unprofitable"—creates a sense of overwhelming exhaustion. The world is not just unpleasant but utterly devoid of meaning, a sentiment that foreshadows Hamlet’s later existential musings ("To be, or not to be"). His disillusionment is further illustrated through the metaphor of the "unweeded garden":

Fie on’t! ah fie! ’tis an unweeded garden,

That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.

This imagery of neglect and decay reflects both the moral corruption of Denmark (embodied by Claudius’s usurpation of the throne) and the broader Renaissance preoccupation with the transience of life. The garden, traditionally a symbol of order and fertility, has become overrun with "rank and gross" weeds, suggesting a world where vice has overtaken virtue. This metaphor aligns with the play’s recurring motifs of disease and rot, reinforcing the idea that Denmark is a poisoned kingdom in need of purging.

Grief, Betrayal, and the Frailty of Woman

The soliloquy takes a deeply personal turn as Hamlet fixates on his mother’s remarriage:

But two months dead: nay, not so much, not two:

So excellent a king; that was, to this,

Hyperion to a satyr...

Hamlet’s grief for his father is compounded by his disgust at Gertrude’s swift remarriage to Claudius. The contrast between King Hamlet ("Hyperion," the radiant sun god of Greek mythology) and Claudius ("a satyr," a lustful, half-beast figure) underscores the degradation Hamlet perceives. His father was a figure of nobility and grace, while Claudius is a debased usurper.

Hamlet’s condemnation of his mother reaches its peak in one of the play’s most infamous lines:

Frailty, thy name is woman!—

This misogynistic outburst reflects both Hamlet’s personal bitterness and the patriarchal attitudes of Shakespeare’s time. Gertrude’s "wicked speed" in remarrying is seen as a betrayal not just of King Hamlet but of womankind itself. The reference to Niobe—a mythological figure who wept endlessly after the death of her children—further highlights Gertrude’s perceived hypocrisy: she mourned extravagantly yet remarried with unseemly haste.

The Paradox of Silence: "But break, my heart; for I must hold my tongue"

The soliloquy concludes with Hamlet’s resignation to silence:

It is not nor it cannot come to good:

But break, my heart; for I must hold my tongue.

This final line encapsulates Hamlet’s tragic dilemma. He recognizes that the situation is irredeemable ("It cannot come to good"), yet he is constrained by political and familial duty from speaking openly. The command to his own heart to "break" suggests both emotional suffocation and an anticipation of further suffering. Unlike later soliloquies where Hamlet debates action, here he is paralyzed by grief and suppression, setting the stage for his ongoing internal conflict.

Historical and Philosophical Contexts

Understanding this soliloquy requires situating it within Renaissance thought. The tension between medieval religiosity and emerging humanist philosophy is evident in Hamlet’s wrestling with suicide. While medieval theology condemned self-destruction, Renaissance thinkers like Montaigne questioned traditional moral absolutes, pondering whether death might be preferable to suffering. Hamlet’s soliloquy embodies this crisis of belief—he is torn between Christian doctrine and his own despair.

Additionally, the political context of Hamlet—written during the reign of Elizabeth I, a time of court intrigue and succession anxieties—resonates with the play’s themes of usurpation and moral decay. The instability of Danish royalty mirrors England’s own anxieties about power and legitimacy.

Conclusion: The Birth of a Modern Psyche

Hamlet’s first soliloquy is more than an expression of grief; it is a microcosm of the play’s central concerns. Through its rich imagery, theological tension, and psychological realism, Shakespeare crafts a portrait of a man alienated from his world, his family, and even his own body. The soliloquy’s enduring power lies in its universality—Hamlet’s anguish speaks to anyone who has grappled with loss, betrayal, or the seeming futility of existence.

In this soliloquy, we see the birth of a distinctly modern consciousness: a mind acutely aware of its own suffering, yet trapped by external and internal constraints. Shakespeare’s genius lies in making Hamlet’s pain not just a dramatic device but a mirror for the human soul. As readers and audiences, we are invited to confront, alongside Hamlet, the unbearable weight of being—and in doing so, we find one of literature’s most profound explorations of what it means to be alive.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.