A Study of Reading Habits

Philip Arthur Larkin

1922 to 1985

When getting my nose in a book

Cured most things short of school,

It was worth ruining my eyes

To know I could still keep cool,

And deal out the old right hook

To dirty dogs twice my size.

Later, with inch-thick specs,

Evil was just my lark.

Me and my cloak and fangs

Had ripping times in the dark

The women I clubbed with sex!

I broke them up like meringues.

Don't read much now: the dude

Who lets the girl down before

The hero arrives, the chap

Who's yellow and keeps the store,

Seem far too familiar. Get stewed:

Books are a load of crap.

Philip Arthur Larkin's A Study of Reading Habits

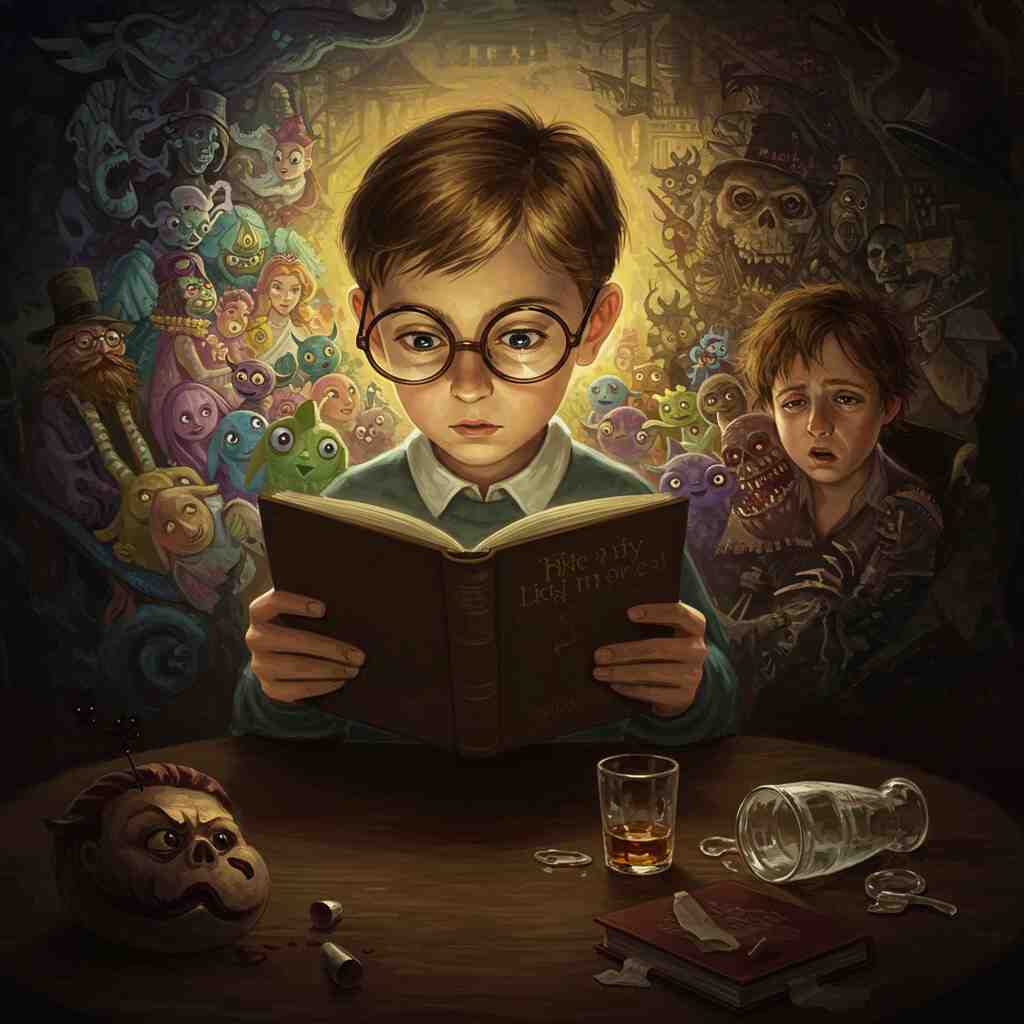

Philip Larkin’s A Study of Reading Habits (1964) is a deceptively simple poem that traces the evolution of a reader’s relationship with books—from childhood escapism to adolescent fantasy and, finally, to disillusioned adulthood. Written in Larkin’s characteristically sardonic and unflinching style, the poem critiques the ways in which literature functions as both a refuge and a delusion, ultimately exposing the harsh realities that books fail to mitigate. Through its three stanzas, the poem moves chronologically, charting the speaker’s shifting attitudes toward reading while subtly revealing deeper anxieties about identity, power, and self-deception.

Larkin, often regarded as one of the most prominent post-war English poets, was a librarian by profession, which adds an ironic layer to his dismissal of books in the final stanza. His poetry frequently explores themes of disappointment, mortality, and the gap between youthful idealism and adult resignation. A Study of Reading Habits is no exception, encapsulating these concerns with brutal honesty and dark humor. This essay will analyze the poem’s structure, imagery, and thematic progression, situating it within Larkin’s broader oeuvre and the cultural context of mid-20th-century Britain.

The Three Stages of Readerly Disillusionment

The poem is divided into three distinct phases, each corresponding to a different life stage: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Each stanza reflects a changing relationship with literature, moving from innocent escapism to violent fantasy before culminating in outright rejection.

1. Childhood: Books as a Shield Against Powerlessness

The first stanza captures the speaker’s childhood experience of reading as a means of empowerment:

When getting my nose in a book

Cured most things short of school,

It was worth ruining my eyes

To know I could still keep cool,

And deal out the old right hook

To dirty dogs twice my size.

Here, books serve as an antidote to the humiliations of youth—particularly the powerlessness of being a child in an adult-dominated world. The phrase "dirty dogs twice my size" suggests bullies or oppressive figures, and reading allows the speaker to imagine himself as a triumphant underdog, capable of retaliating with an "old right hook." The physical toll of reading ("ruining my eyes") is presented as a worthy sacrifice for the psychological relief it provides.

This stanza reflects a common childhood experience: literature as a form of wish fulfillment. The speaker’s fantasies are straightforwardly heroic, rooted in physical dominance—a stark contrast to the more complex, morally ambiguous fantasies of later stanzas. The language is colloquial and energetic, mirroring the uncomplicated bravado of youth.

2. Adolescence: The Dark Turn of Fantasy

The second stanza marks a shift into adolescence, where the escapism of reading takes on a more sinister tone:

Later, with inch-thick specs,

Evil was just my lark.

Me and my cloak and fangs

Had ripping times in the dark.

The women I clubbed with sex!

I broke them up like meringues.

The speaker’s "inch-thick specs" suggest both intellectualism and physical frailty, reinforcing the idea that reading remains a compensatory mechanism for inadequacies. However, the nature of the fantasies has changed—no longer the noble hero, the speaker now identifies with Gothic villains, reveling in "cloak and fangs." The phrase "Evil was just my lark" implies a playful indulgence in transgression, but the imagery quickly turns disturbing.

The most striking—and unsettling—lines are "The women I clubbed with sex! / I broke them up like meringues." Here, the speaker’s fantasy is not just violent but explicitly misogynistic, reducing women to fragile objects to be destroyed. The simile "like meringues" is particularly jarring, combining a delicate, sweet image with brutality. This reflects a troubling adolescent mindset where power is equated with sexual domination, a theme Larkin revisits in other poems (Sunny Prestatyn, for instance, depicts a similar degradation of the female form).

This stanza critiques not just the speaker’s fantasies but also the cultural narratives that feed them. The Gothic tropes (cloak and fangs) suggest the influence of pulp fiction or horror stories, which often sensationalize violence and eroticize power. The adolescent reader, rather than finding moral guidance in books, instead indulges in toxic fantasies—raising questions about the responsibilities of literature itself.

3. Adulthood: The Collapse of Illusion

The final stanza delivers the poem’s bleak conclusion:

Don’t read much now: the dude

Who lets the girl down before

The hero arrives, the chap

Who’s yellow and keeps the store,

Seem far too familiar. Get stewed:

Books are a load of crap.

Here, the speaker abandons reading entirely, not because he has outgrown it, but because he now recognizes himself in the most unflattering literary archetypes. The "dude / Who lets the girl down" and the "chap / Who’s yellow and keeps the store" are cowardly, passive figures—far from the heroic or villainous roles he once identified with. The realization that he is not the protagonist of his own story, but rather a marginal, ignoble character, is crushing.

The dismissive final line—"Books are a load of crap."—is deliberately crude, rejecting intellectualism in favor of intoxication ("Get stewed"). This echoes Larkin’s recurring theme of disillusionment: if books once offered escape, they now only reflect the speaker’s failures. The shift from elaborate metaphors ("broke them up like meringues") to blunt vernacular ("a load of crap") mirrors the collapse of literary pretense into raw, unfiltered cynicism.

Literary and Cultural Context

Larkin’s poem can be read as a response to the mid-20th-century crisis of faith in literature. The post-war period saw increasing skepticism toward grand narratives, and Larkin—often associated with the Movement poets—rejected Romantic idealism in favor of stark realism. His work frequently undermines traditional literary consolations, and A Study of Reading Habits is a prime example.

The poem also engages with the psychological function of reading. In The Uses of Enchantment (1976), Bruno Bettelheim argues that fairy tales help children navigate fears and desires. Larkin’s poem inverts this: rather than providing healthy catharsis, books feed destructive fantasies before ultimately failing to sustain the reader in adulthood.

Additionally, the poem critiques the gendered nature of literary identification. The speaker’s adolescent fantasies are hypermasculine, reflecting cultural narratives that equate masculinity with dominance. His eventual disillusionment stems from recognizing that he does not measure up to these impossible ideals—a theme Larkin explores elsewhere, such as in This Be The Verse, where he similarly dismantles idealized notions of family and selfhood.

Conclusion: The Failure of Escapism

A Study of Reading Habits is not just a poem about books; it is a meditation on the ways we use narratives to construct—and deceive—ourselves. The speaker progresses from seeing literature as a tool of empowerment to recognizing it as a mirror of his own inadequacies. The final rejection of reading is not a triumph of realism over fantasy, but a surrender—an admission that neither books nor alcohol can ultimately compensate for life’s disappointments.

Larkin’s genius lies in his ability to convey profound disillusionment with biting wit and rhythmic precision. The poem’s dark humor makes its despair palatable, even entertaining, but the underlying message is deeply pessimistic: if literature once offered refuge, adulthood reveals it as just another false comfort. In this sense, A Study of Reading Habits is not just a personal confession but a broader commentary on the limitations of art itself—an idea as unsettling as it is unforgettable.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.