Confined Love

John Donne

1572 to 1631

Some man unworthy to be possessor

Of old or new love, himselfe being false or weake,

Thought his paine and shame would be lesser,

If on womankind he might his anger wreake,

And thence a law did grow,

One might but one man know;

But are other creatures so?

Are Sunne, Moone, or Starres by law forbidden,

To smile where they list, or lend away their light?

Are birds divorc'd, or are they chidden

If they leave their mate, or lie abroad a night?

Beasts doe no joyntures lose

Though they new lovers choose,

But we are made worse then those.

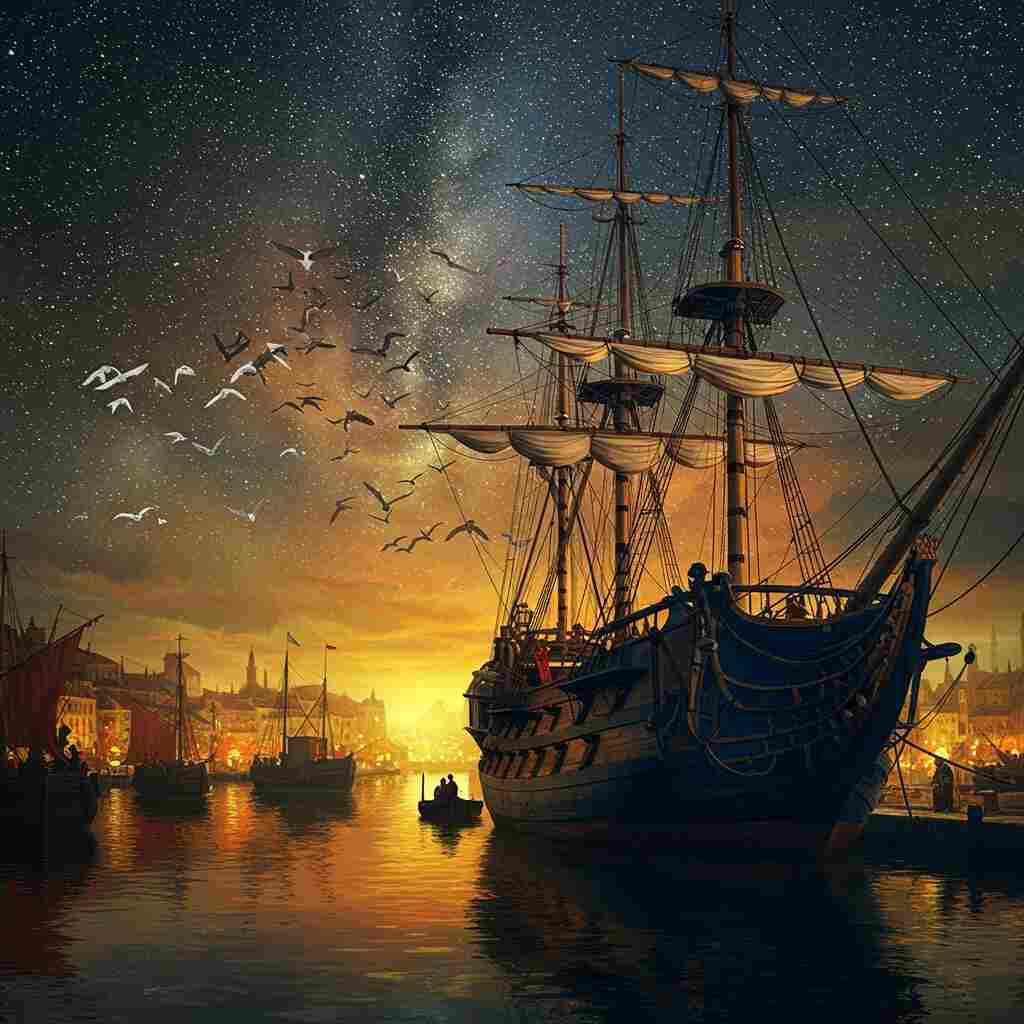

Who e'r rigg'd faire ship to lie in harbors,

And not to seeke new lands, or not to deale withall?

Or built faire houses, set trees, and arbors,

Only to lock up, or else to let them fall?

Good is not good, unlesse

A thousand it possesse,

But doth wast with greedinesse.

John Donne's Confined Love

John Donne's "Confined Love" stands as a provocative exploration of sexual freedom and the constraints of matrimonial fidelity in early modern England. The poem embodies Donne's characteristic intellectual agility and his willingness to challenge the social and religious orthodoxies of his time. Composed during the early seventeenth century, "Confined Love" belongs to Donne's canon of love poetry, though its placement within the traditional categories of his work—whether as an early libertine composition or a more mature philosophical reflection—remains a subject of scholarly debate. In this analysis, I will examine how Donne employs a sophisticated rhetorical strategy to question the moral validity of monogamy through a series of natural analogies, ultimately proposing that societal restrictions on love represent an unnatural constraint that warps human potential and contradicts the abundance principle evident in the natural world.

The poem merits close attention not merely for its provocative content, but for how it illuminates Donne's position within the complex intellectual landscape of Renaissance England. Through "Confined Love," we encounter a poet negotiating between medieval scholasticism and emergent humanist thought, between Catholic sensibilities and Protestant reforms, and between courtly traditions and new modes of intimate expression. My analysis will consider the poem's historical context, its rhetorical structure, its place within Donne's broader oeuvre, and its engagement with contemporary philosophical and theological debates about the nature of love, desire, and human sexuality.

Historical and Biographical Context

To understand "Confined Love" fully requires situating it within the complex tapestry of Donne's life and times. Born into a Catholic family in 1572, when adherence to the old faith carried significant social and legal penalties in Protestant England, Donne navigated a precarious path between religious traditions. His early education, likely influenced by Jesuit teachings, would have exposed him to scholastic argumentation—a method evident in the poem's logical progression and use of analogical reasoning. His subsequent studies at Oxford and Cambridge, though incomplete due to his refusal to take the Oath of Supremacy, further developed his intellectual versatility.

Donne's early career as a gentleman adventurer and aspiring courtier coincided with his composition of love poetry that often challenged conventional morality. His poems from this period, sometimes called the "Songs and Sonnets," frequently display a libertine sensibility that valorizes sexual conquest and emotional detachment. However, Donne's clandestine marriage to Anne More in 1601—a union that cost him his career prospects and temporarily landed him in prison—marks a significant biographical turning point that complicates our reading of "Confined Love."

Whether the poem predates this personal crisis or reflects upon it from a later vantage point significantly affects its interpretation. If composed during his libertine youth, the poem might represent a genuine argument against monogamy. If written after his marriage, it could function as a rhetorical exercise, a deliberately provocative stance adopted to showcase his intellectual dexterity rather than express his mature convictions. Given Donne's eventual ordination as an Anglican priest in 1615 and his subsequent reputation for profound sermons on divine love, the poem also invites consideration of how his understanding of human and divine love evolved throughout his life.

The social context of early modern marriage further illuminates the poem's significance. Marriage in Elizabethan and Jacobean England represented not merely a personal commitment but a social and economic institution essential to the transmission of property and the maintenance of patriarchal authority. Wives were legally subordinate to husbands under the doctrine of coverture, and female adultery was punished more severely than male infidelity. Against this backdrop, Donne's challenge to monogamy carries political implications that extend beyond the merely personal.

Rhetorical Structure and Argumentative Strategy

"Confined Love" exemplifies Donne's masterful rhetorical technique. The poem employs a sophisticated argumentative structure that begins by identifying an opponent, proceeds through a series of natural analogies, and culminates in a philosophical principle about the nature of goodness itself. This progression reveals Donne's scholastic training and his talent for constructing persuasive arguments.

The opening stanza establishes the poem's confrontational premise by attributing the law of monogamy to "Some man unworthy to be possessor / Of old or new love, himselfe being false or weake." This ad hominem attack immediately challenges the credibility of whoever established monogamy as a social expectation. The rhetorical strategy here positions the subsequent argument as a correction to an illegitimate authority rather than a mere transgressive impulse. By claiming that this unidentified legislator created the rule out of personal inadequacy—being "false or weake"—and a desire to "his anger wreake" upon women, Donne immediately frames monogamy as a product of male insecurity rather than divine ordination or natural law.

The second stanza shifts to a series of rhetorical questions that invoke natural analogies: the heavenly bodies (sun, moon, stars), birds, and beasts. Each question implicitly argues that no other element of creation is bound by monogamous restrictions. The celestial bodies "smile where they list" and freely "lend away their light." Birds face no punishment if they "leave their mate, or lie abroad a night." These analogies construct what rhetoricians would recognize as an argument from nature—if the natural world, presumably designed by God, operates according to principles of freedom, then human restrictions on love contradict the divine pattern established in creation.

The final stanza transitions to analogies drawn from human endeavors—shipping, architecture, and gardening—suggesting that restricting love to a single object contradicts not only nature but human productive practices as well. The poem concludes with a philosophical maxim: "Good is not good, unlesse / A thousand it possesse, / But doth wast with greedinesse." This concluding assertion elevates the argument from a specific complaint about sexual restrictions to a universal principle about the nature of goodness itself, suggesting that true value multiplies through sharing rather than diminishing.

This carefully constructed rhetorical progression reveals Donne's intellectual agility and his ability to deploy multiple argumentative strategies—appeals to nature, analogy, and philosophical principle—in service of a provocative thesis.

Literary Devices and Poetic Craft

The poem's language reveals Donne's characteristic blend of colloquial directness and intellectual complexity. The opening stanza's "Some man unworthy" immediately establishes a conversational tone that makes the reader complicit in the critique of this unnamed authority. Yet this apparent simplicity coexists with sophisticated wordplay, as in "old or new love," which simultaneously evokes traditional versus innovative conceptions of love and the chronological progression of romantic attachments.

Donne's mastery of metaphor drives the poem's argumentative force. The celestial metaphors in the second stanza—sun, moon, and stars that "smile where they list"—anthropomorphize natural phenomena in a way that validates human emotional variability. These metaphors operate within the Renaissance cosmological framework, where celestial movements were understood as both literal planetary motions and as symbolic of higher orders of meaning. By invoking this cosmological system, Donne implicitly suggests that sexual freedom belongs to the divinely ordained natural order.

The maritime and architectural metaphors of the final stanza—ships meant to explore "new lands" rather than remain harbored, houses built not "only to lock up"—extend the poem's conceptual scope from natural to human-created systems. These metaphors introduce economic and colonial valences: ships venture forth for commerce and conquest; houses and gardens represent investment and cultivation. By drawing these parallels, Donne suggests that emotional and sexual constraint contradicts not only nature but also the productive economic imperative of his mercantile age.

Sound patterns reinforce the poem's argumentative thrust. The predominance of question marks in the second stanza creates a rhythmic insistence that challenges readers to defend monogamy against the weight of natural evidence. The final stanza's definitive declarations, by contrast, land with emphatic certainty, particularly in the epigrammatic final three lines where the shortened meter creates a sense of conclusiveness.

Thematic Analysis

The Politics of Sexual Freedom

At its core, "Confined Love" presents a radical critique of monogamy as an unnatural restriction imposed by human artifice rather than divine design. This position carries significant political implications in an era when marriage constituted not merely a personal arrangement but a fundamental social institution that structured property relations and dynastic continuity. By questioning the legitimacy of monogamous marriage, Donne implicitly challenges the patriarchal social order that such marriages sustained.

The poem's opening attribution of the monogamy law to a man who is "false or weake" establishes gender politics as central to its concern. The suggestion that monogamy represents a form of revenge "on womankind" positions the poem as surprisingly aware of how sexual double standards functioned as instruments of gender control. However, this seemingly proto-feminist perspective requires cautious interpretation. While Donne questions restrictions on female sexuality, he does so within a framework that still conceptualizes women as objects to be possessed—"possessor / Of old or new love"—rather than as autonomous agents.

Natural Law Versus Social Convention

A central thematic tension in "Confined Love" concerns the relationship between natural impulses and social constraints. Donne's series of analogies to celestial bodies, birds, and beasts constructs an argument that human sexual restrictiveness contradicts natural patterns. This appeal to nature as a standard against which human customs should be measured reflects Renaissance humanist approaches to ethics, which often sought to ground moral principles in observations of the natural world rather than solely in religious doctrine.

However, the poem's position becomes more complex when we consider it against the backdrop of Donne's eventual religious career. Christian theology, particularly in its Augustinian formulation that Donne would have encountered, typically distinguishes between prelapsarian nature (before the Fall) and postlapsarian nature (after the Fall). In this framework, human desire is understood as corrupted by original sin, meaning that "natural" impulses may require restraint rather than expression. The poem's untroubled equation of natural inclination with moral good thus represents either a deliberate rejection of this theological position or a rhetorical stance that prioritizes persuasive force over doctrinal consistency.

Abundance Versus Scarcity

The poem's concluding maxim—"Good is not good, unlesse / A thousand it possesse, / But doth wast with greedinesse"—articulates a philosophy of abundance that contrasts sharply with notions of sexual scarcity implied by monogamous restriction. This principle suggests that goodness multiplies rather than diminishes through sharing, an idea that has both economic and theological resonances.

Economically, the abundance principle aligns with emergent capitalist values that emphasized growth and expansion over medieval ideals of moderation and sufficiency. The trading ship that seeks "new lands" evokes the colonial enterprises of Donne's era, suggesting a parallel between economic and erotic exploration. However, the final reference to "greedinesse" complicates this reading, introducing a moral critique of excessive acquisition that seems at odds with the poem's advocacy for sexual freedom.

Theologically, the abundance principle evokes the Christian concept of grace—divine love that multiplies through giving rather than diminishing. This creates an intriguing tension: Donne appropriates a theological principle traditionally applied to divine love to justify what conventional Christian morality would condemn as sinful human desire. This conceptual maneuver exemplifies Donne's characteristic technique of repurposing religious language and concepts for erotic contexts, a practice that earned him both admiration for his intellectual daring and criticism for perceived blasphemy.

Comparative Context

Situating "Confined Love" within broader literary traditions enriches our understanding of its significance. The poem's argument against monogamy connects to a long tradition of amatory verse that celebrates libertine values, from classical sources like Ovid's "Amores" to contemporary Renaissance texts. However, Donne's approach differs significantly from both ancient and contemporary models in its intellectual rigor and rhetorical sophistication.

Unlike Ovid, whose "Amores" often presents libertinism as a youthful rebellion against staid morality, Donne constructs a quasi-philosophical defense based on natural law and the metaphysics of goodness. Unlike courtly love poets who often celebrated extramarital desire within a framework that still nominally respected marriage as an institution, Donne directly challenges the validity of monogamous restriction itself.

Compared to his contemporaries, Donne's approach in "Confined Love" reveals both commonalities and distinctions. Like other metaphysical poets such as Andrew Marvell, Donne employs elaborate conceits and paradoxical reasoning to challenge conventional wisdom. However, while Marvell's "To His Coy Mistress" uses the urgency of mortality to persuade a reluctant lover, Donne's argument in "Confined Love" operates at a more abstract level, questioning the foundational principles of sexual morality rather than focusing on a specific seduction.

Within Donne's own oeuvre, "Confined Love" reveals interesting tensions and continuities. The poem's argumentative libertinism contrasts sharply with the profound spiritual devotion expressed in his Holy Sonnets and religious writings. Yet its intellectual playfulness and rhetorical ingenuity connect it to Donne's other works, both sacred and profane. The poem exemplifies what critics have identified as Donne's characteristic concern with the relationship between physical and metaphysical realities, between embodied experience and abstract principle.

Reception and Critical History

The reception history of "Confined Love" reflects broader patterns in Donne's critical fortune. During the Restoration and eighteenth century, when poetic tastes favored more regular forms and decorous expression, Donne's metaphysical complexities fell into relative obscurity. The Victorian era, with its emphasis on moral propriety, further marginalized poems like "Confined Love" that seemed to advocate sexual license.

Donne's critical rehabilitation began in earnest with T.S. Eliot's influential 1921 essay "The Metaphysical Poets," which praised precisely the qualities that earlier critics had condemned—the fusion of intellectual complexity with emotional intensity that Eliot termed "unified sensibility." Subsequent New Critical approaches, with their emphasis on close reading and the autonomy of the text, found in Donne's poetry a rich field for analysis, though they sometimes downplayed the historical and biographical contexts essential to understanding a poem as politically charged as "Confined Love."

More recent feminist and gender-focused criticism has brought renewed attention to poems like "Confined Love" that explicitly address sexual politics. Critics such as Achsah Guibbory have examined how Donne's poetry negotiates the gendered power dynamics of early modern England, revealing tensions between his intellectual radicalism and his participation in patriarchal assumptions. Post-structural approaches have further illuminated how Donne's poetry destabilizes fixed categories of meaning, creating interpretive ambiguities that resist definitive resolution.

Within this critical evolution, "Confined Love" occupies a particularly interesting position. Its explicit challenge to monogamy makes it more overtly transgressive than many of Donne's better-known love poems, while its sophisticated argumentation demonstrates the intellectual qualities that have secured his canonical status. The poem thus serves as a touchstone for broader debates about Donne's place in literary history—whether as a subversive voice challenging social conventions or as an intellectual showman whose provocations serve primarily rhetorical rather than revolutionary ends.

Conclusion

"Confined Love" exemplifies John Donne's poetic genius through its fusion of intellectual rigor and emotional provocativeness. The poem deploys a sophisticated rhetorical strategy to challenge one of society's fundamental institutions, marshaling evidence from nature, human enterprise, and philosophical principle to argue against monogamous restriction. Whether read as a sincere libertine manifesto or as a rhetorical exercise displaying Donne's intellectual versatility, the poem reveals the complex interplay of tradition and innovation, conformity and rebellion, that characterizes his work.

The poem's enduring significance lies partly in how it illuminates the tensions of Donne's historical moment—a transitional period when medieval certainties were giving way to new modes of thought, when religious orthodoxies faced challenges from humanist inquiry, and when traditional social structures encountered emergent individualism. "Confined Love" captures these tensions through its questioning of established sexual morality, its appeal to nature as a standard for human behavior, and its implicit challenge to institutions that restrict desire.

For contemporary readers, the poem offers valuable insight into how rhetorical strategies can be deployed to challenge entrenched social norms. Its argumentative progression—from identifying a problem, through natural analogies, to philosophical principle—demonstrates the power of carefully structured reasoning to question seemingly self-evident truths. While its specific conclusion about monogamy may or may not persuade modern readers, its method of interrogating received wisdom through rigorous intellectual examination remains instructive.

In the end, "Confined Love" stands as a testament to Donne's ability to fuse intellectual complexity with emotional and political urgency. The poem exemplifies what makes Donne's work continually relevant: his willingness to question orthodoxies, his sophisticated rhetorical craft, and his profound engagement with the fundamental human experiences of desire, restriction, and the search for authentic value in a world of competing claims on our loyalty and love.

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem critique. This exercise is designed for classroom use.